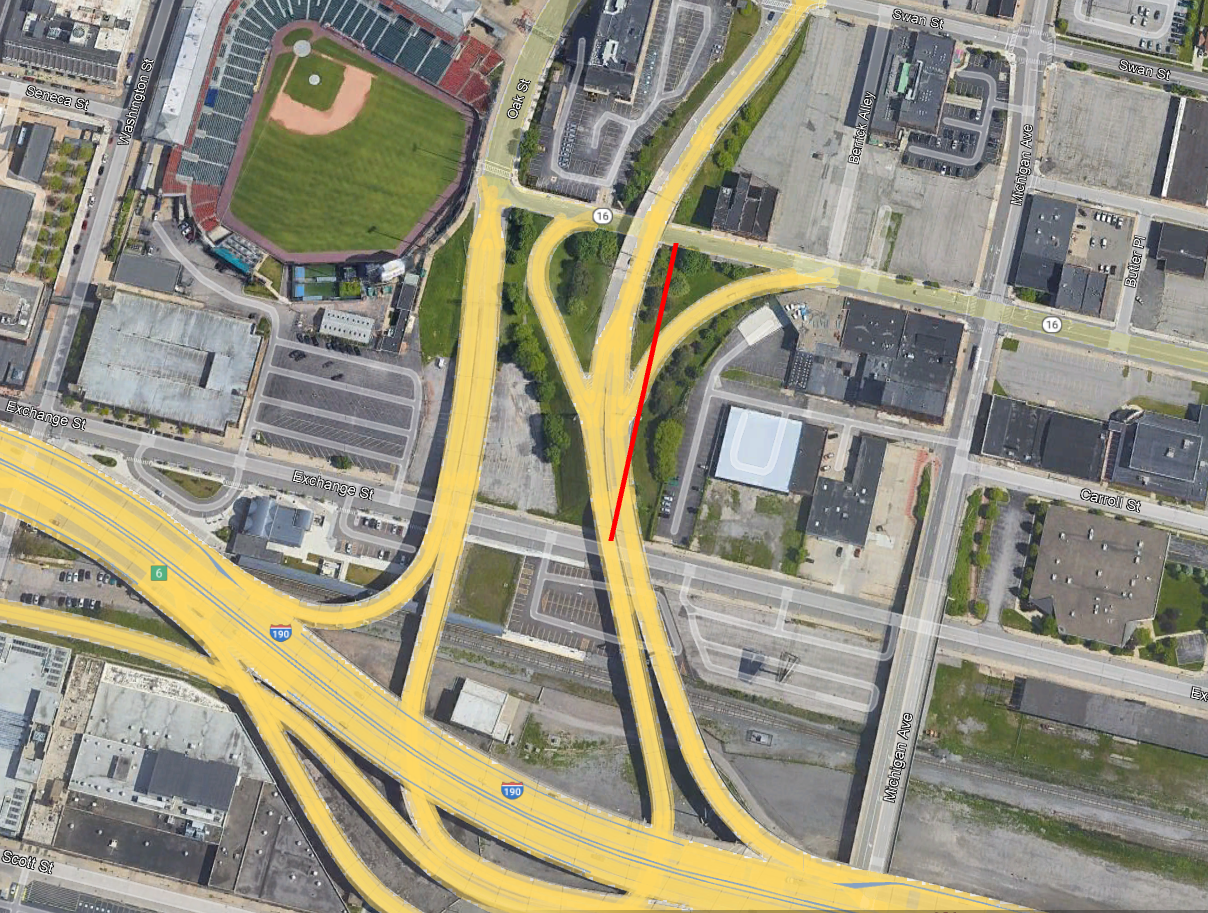

The former location of Wells Street is shown in red.

Wells Street is a street that is no longer extant in Downtown Buffalo. It formerly ran for two blocks between Exchange and Seneca Street. The former location of Wells Street is now hidden underneath the Elm Street exit ramps from the I-190. Wells Street was once an important business center in Buffalo, serving both visitors and industry due to its location close to the railroads.

Many often believe that Wells Street is named after Henry Wells. Henry Wells helped found Wells Fargo alongside William Fargo. Henry Wells lived in Auhoorora in Cayuga County, New York. Wells College is named for Henry Wells. However, Wells Street here in Buffalo is named after Chandler J. Wells. I could not find any relationship between Henry and Chandler, though they may be related many generations back.

The Early Life of Chandler Wells

The Buffalo Wells family – Joseph Wells and his wife Prudence – came to Buffalo around 1797 from Rhode Island. There wasn’t much happening here in Buffalo, so they settled in Brantford, Ontario, where Prudence’s sister lived. They came back to Buffalo around 1802. Joseph and Prudence had their first son, Aldrich, in 1802 after returning to Buffalo. Some reports say that Aldrich Wells was the first white male born in Buffalo, but there are several disputed claims to that title. Joseph and Prudence had eleven children – six sons and five daughters. Their seventh child, Chandler, is the namesake of the street.

Chandler Joseph Wells was born in Utica, New York, in June 1814. The Wells family had fled to Utica after the Burning of Buffalo on December 30, 1813. During the War of 1812, Joseph Wells served as a Captain and later a Major in the militia. Shortly after Chandler’s birth, the Wells family returned to Buffalo with baby Chandler. The Wells family lived at 150 Swan Street. In 1815, Joseph Wells built a tannery on Main Street near Allen Street, where he also operated a farm and made bricks.

Chandler Joseph Wells was born in Utica, New York, in June 1814. The Wells family had fled to Utica after the Burning of Buffalo on December 30, 1813. During the War of 1812, Joseph Wells served as a Captain and later a Major in the militia. Shortly after Chandler’s birth, the Wells family returned to Buffalo with baby Chandler. The Wells family lived at 150 Swan Street. In 1815, Joseph Wells built a tannery on Main Street near Allen Street, where he also operated a farm and made bricks.

Chandler attended private schools when he was young. At age 17, Chandler became a joiner’s apprentice, finding employment with Benjamin Rathbun. He later worked for John Drew, who saw potential in Mr. Wells and put him in charge of constructing a building at Pearl and Tupper Streets.

In 1835, Mr. Wells partnered with William Hart as contractors and builders. The partnership lasted for twenty years, and they were very successful. At one time, they owned three sawmills and built many buildings around Western New York. Among their buildings were the State Arsenal on Broadway, built in 1857, and the Dart Mansion at Niagara and Georgia Streets.

Grain Elevator Entrepreuneur

In 1857, Mr. Wells became interested in grain elevators. His brother William was an elevator foreman. Mr. Wells felt he could improve Joseph Dart’s elevator design. The Wells Elevator was built in 1857-1858 and had a storage capacity of 100,000 bushels, double that of the Dart Elevator. It could transfer nearly six times the amount of grain in an hour. The elevator, known as the Wells Elevator (later became the Wheeler Elevator in 1884 and was replaced by the concrete Wheeler Elevator, constructed in 1909 and now part of Buffalo Riverworks), was located across the river from the New York Central Railroad freight house on Ohio Street.

C.J. Wells Elevator, between Ohio and Indiana Streets…now the location of the DL&W Terminal. Source: Buffalo and Erie County Public Library.

In August 1860, Chandler Wells leased what was known as Coburn Square, located at Buffalo Creek, Ohio (now South Park Ave) and Indiana Streets. He built the Coburn Elevator here. It was destroyed by fire in 1863. In September 1860, he built the CJ Wells Elevator to replace the Coburn Elevator on the site with some additional property he purchased. The CJ Wells Elevator was built with stone, brick and lumber. It was designed to be a model elevator of its day. It had a capacity of 350,000 bushels and could elevate 8,000 bushels an hour. The CJ Wells elevator burned down in 1912, and the DL&W Railroad Station was constructed on the site in 1917 (now the location of the NFTA Shops/Rail Yard).

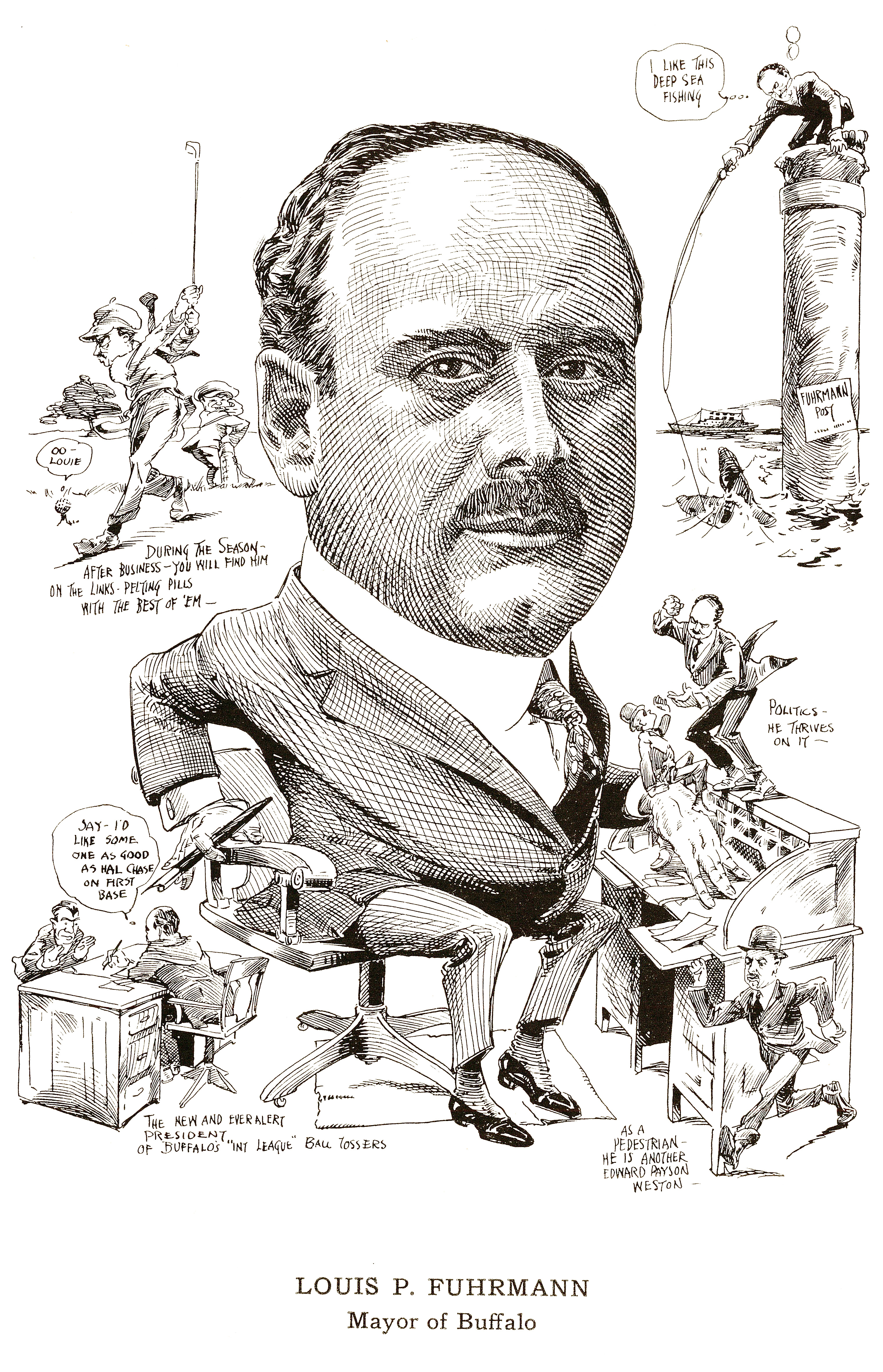

Political Career of Chandler Wells

In 1854, Mr. Wells was elected Alderman for the 2nd Ward. He was continuously elected for seven years. In 1861, Wells was the unanimous Union Republican candidate for Mayor. He was defeated by William Fargo, 6,431 to 5,986 votes. In 1865, he was again named the Union Republican candidate, running again against William Fargo, who was looking to win his third term as mayor. On November 7, 1865, Mr. Wells defeated Mr. Fargo 5,570 to 5,348. On election night, a group of his supporters went to Mr. Wells’ Swan Street home and saluted him with a small cannon.

Mayor Wells was mayor during the Fenian Uprising in 1866. Thousands of Fenians gathered in Buffalo, planning to enter Canada and destroy the Welland Canal, which would have crippled the Canadian trade. Mayor Wells kept the mayors of Hamilton and Toronto informed of the movements of the Fenians. General Grant arrived on the Battleship Michigan to guard the Niagara River. The situation lasted for about a week.

In September 1866, General Ulysses S Grant, President Andrew Johnson and other dignitaries were guests at Mayor Wells’ home. Mayor Wells did not seek a second term in office, deciding instead to retire. Following his retirement, Mayor Wells served as commissioner of the first Board of Water Commissioners and held the position for six years. During his time on the Board, the inlet pier and tunnel were built for Buffalo Water Works. Many people at the time opposed the plan for the waterworks, thinking it impractical. Mayor Wells threw his time and money into the project and worked hard to get the water system built. The City later saw the value in the water inlet, and Mr. Wells was reimbursed for his expenses. He is sometimes referred to as “the father of the waterworks.”

Chandler Wells also served as a founder and director of the Erie County Savings Bank, the Young Men’s Association, the Buffalo Historical Society, the Falconwood and Beaver Island Clubs, and the Buffalo Club. Mayor Wells was also fond of horses. He helped found the Buffalo Driving Park, one of the first organizations of its kind (horse-driving, not car-driving, FYI), and served as President for 15 years. Mr. Wells was a founding member of the Board of the Buffalo Juvenile Asylum in 1856. In 1862, Mr. Wells helped organize the Buffalo Academy of Fine Arts (now the AKG Museum).

The Wells Family

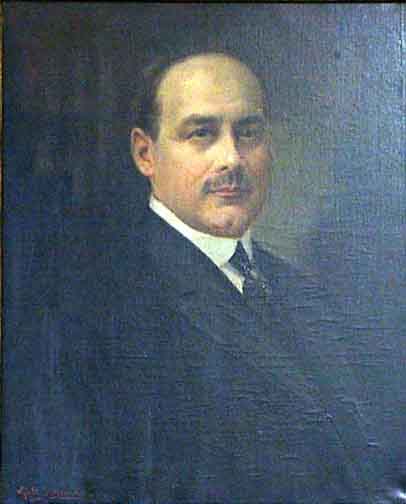

Portrait of Elizabeth Wells, daughter of Chandler. Source: Buffalo Times.

Mr. Wells married Susan Wheeler in April 1837. The Wells had two children. The first, Theodore, died after just six weeks in 1838. The second child, daughter Elizabeth, died of Cholera in 1854 at age 16. Her death was one of the reasons Chandler Wells cared so deeply about clean water and invested in the waterworks. After the death of their daughter, Susan and Chandler’s niece, Lucy Ann Wells, lived with them. Lucy was the daughter of Chandler’s brother, John. Lucy got married in 1847 to Merrit W Green. Lucy and Merrit had two daughters – Jeannie and Elizabeth. Jeannie and Elizabeth were Chandler and Susan’s grand-nieces, but they were eventually adopted by Chandler and Susan when their parents moved to Michigan. Jeannie and Elizabeth took the Wells name and were treated as a part of the Wells family.

In 1858, the Wells family built a red brick house at 77 Swan Street (near Oak Street). At the time, Swan Street was the fashionable neighborhood of Buffalo, but eventually, the street changed to a business district; many families began to move to places like Delaware Avenue. In the 1860s, the Wells Family built a house at 685 Main Street. The house on Main Street is now the location of Town Ballroom. In 1860, the family lived with servants Mary Ann Higgins, a 12-year-old girl, and Fanny Castillo, a 20-year-old woman who worked as a cook. In 1870, Fanny was still working for the family as a cook, along with Eliza Killian, a 21-year-old domestic servant. In 1880, Fanny was still working for the family, along with 30-year-old Margaret O’Brien.

Chandler Wells House on Swan Street. Source: Buffalo Times.

Chandler Wells House on Main Street near Tupper. Source: Buffalo Times.

Mayor Wells Grave in Forest Lawn.

Mayor Wells died on February 4, 1887, after suffering from rheumatism of the heart for more than 13 weeks. His obituary in the Buffalo News called him “a man of quick perceptions, rare judgment and unflinching integrity, with energy and perseverance far beyond the average; a bluff and outspoken manner to strangers, behind which, however, lay a heart good humor and a kindly generous heart.” He is buried in Forest Lawn Cemetery. Mrs. Wells died in October 1892. The house at 685 Main Street was sold in February 1893 to the “Business Mens Investment Association.” The house was rented out to Dr. L. E. DeCouriander and became the Buffalo Sanitorium/Invalids’ Hotel. The former house site is now the location of Town Ballroom.

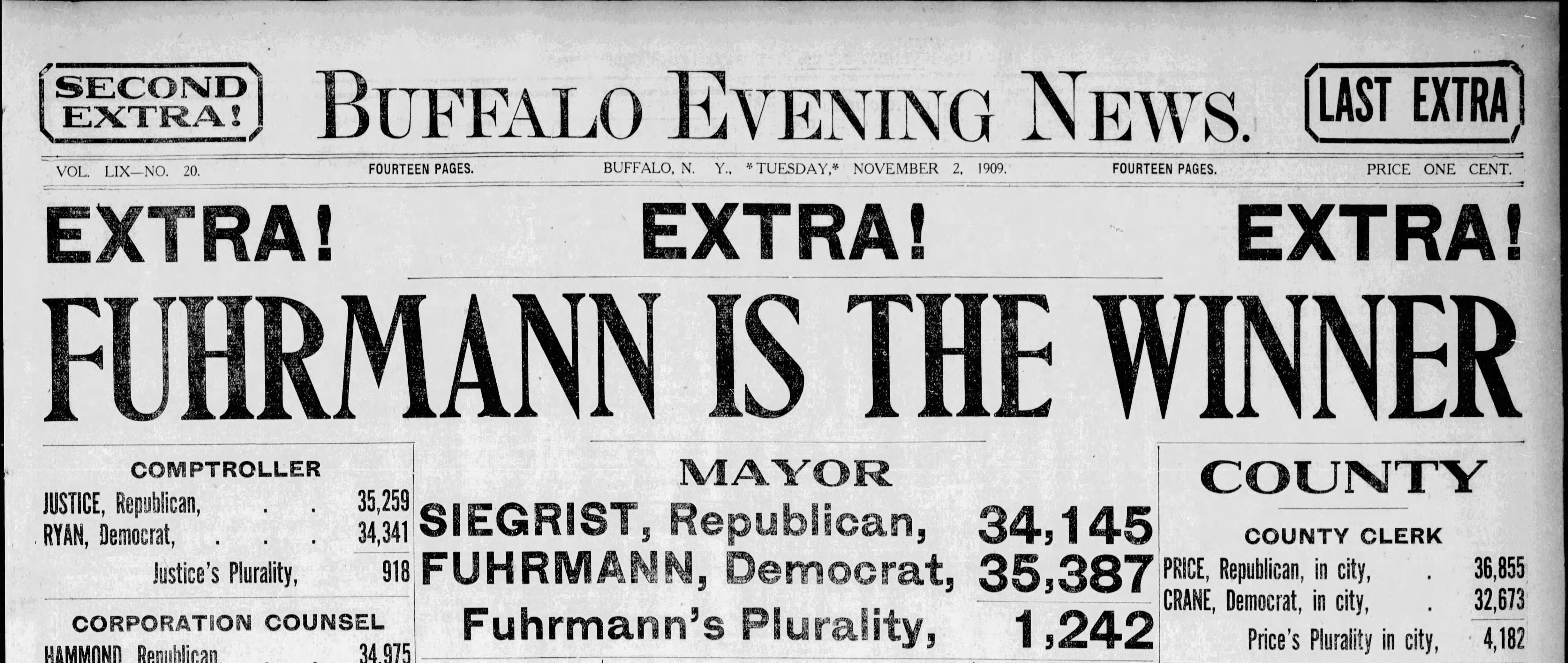

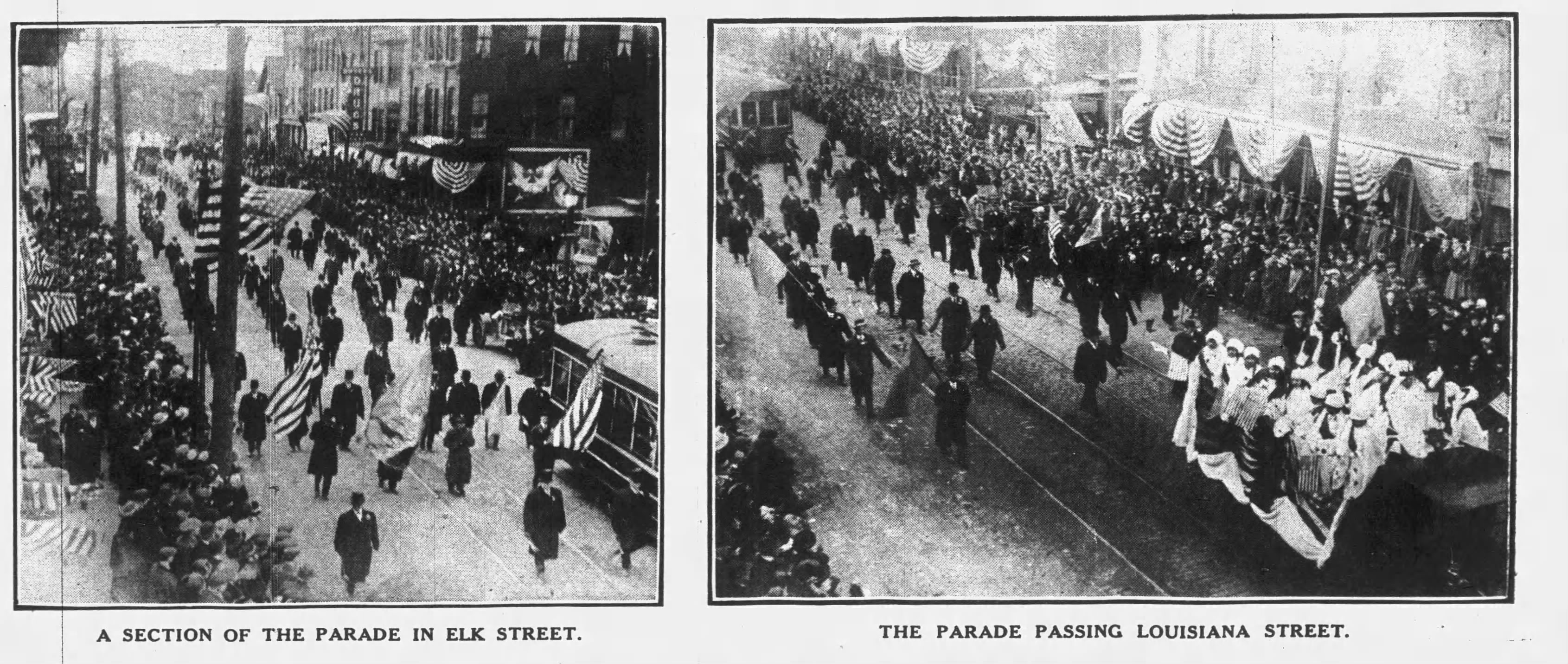

The Great Wells Street Fire of 1889

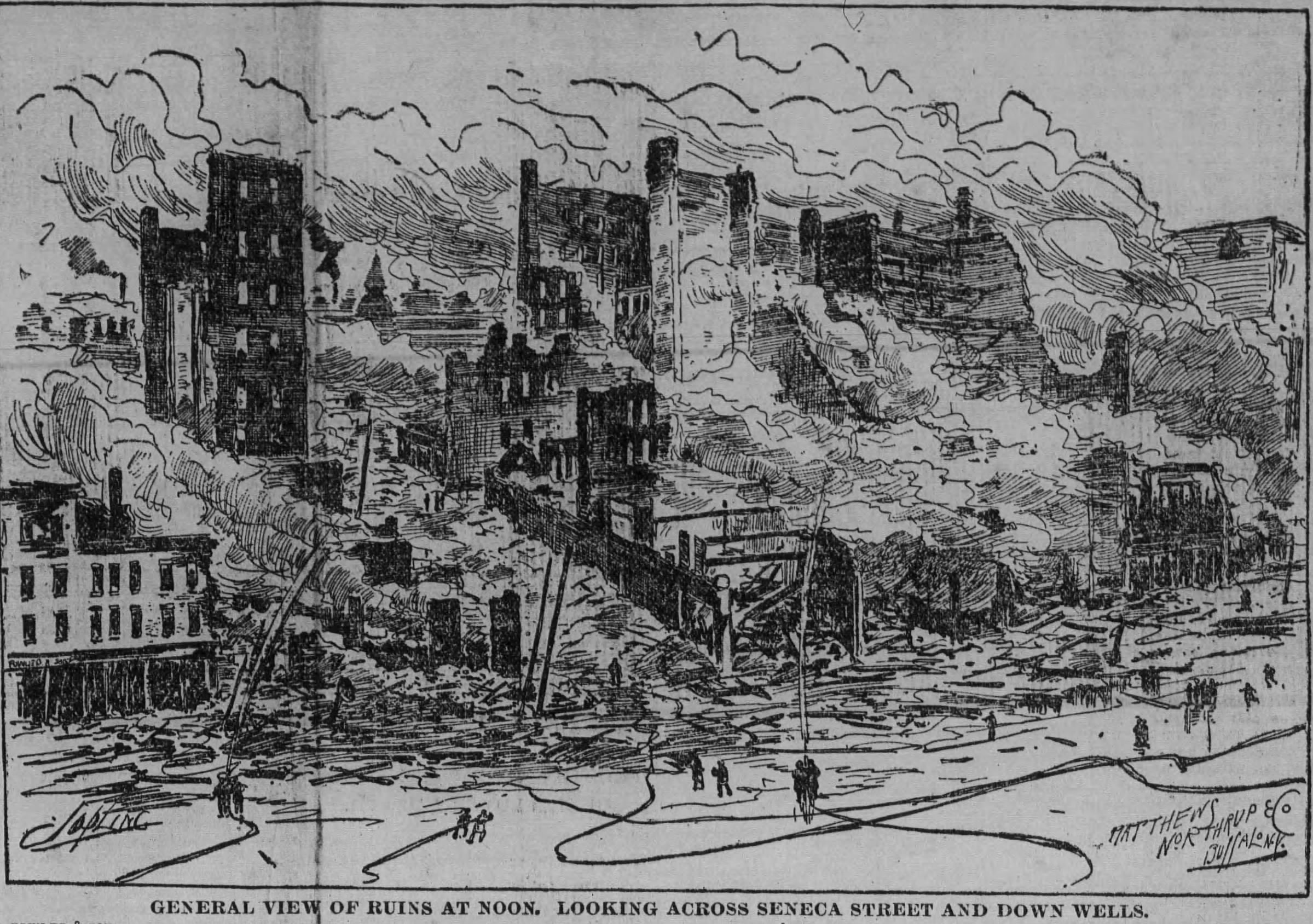

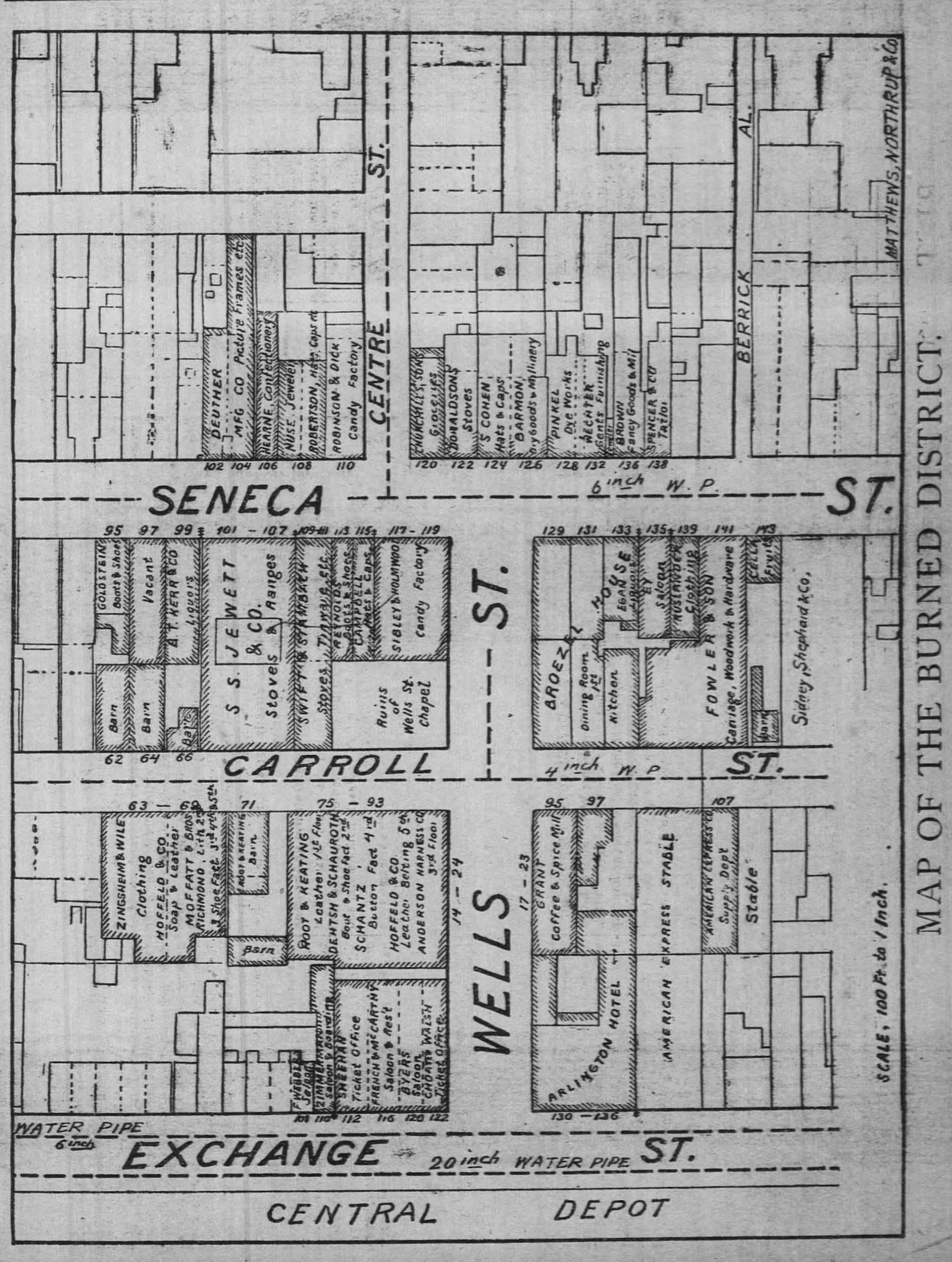

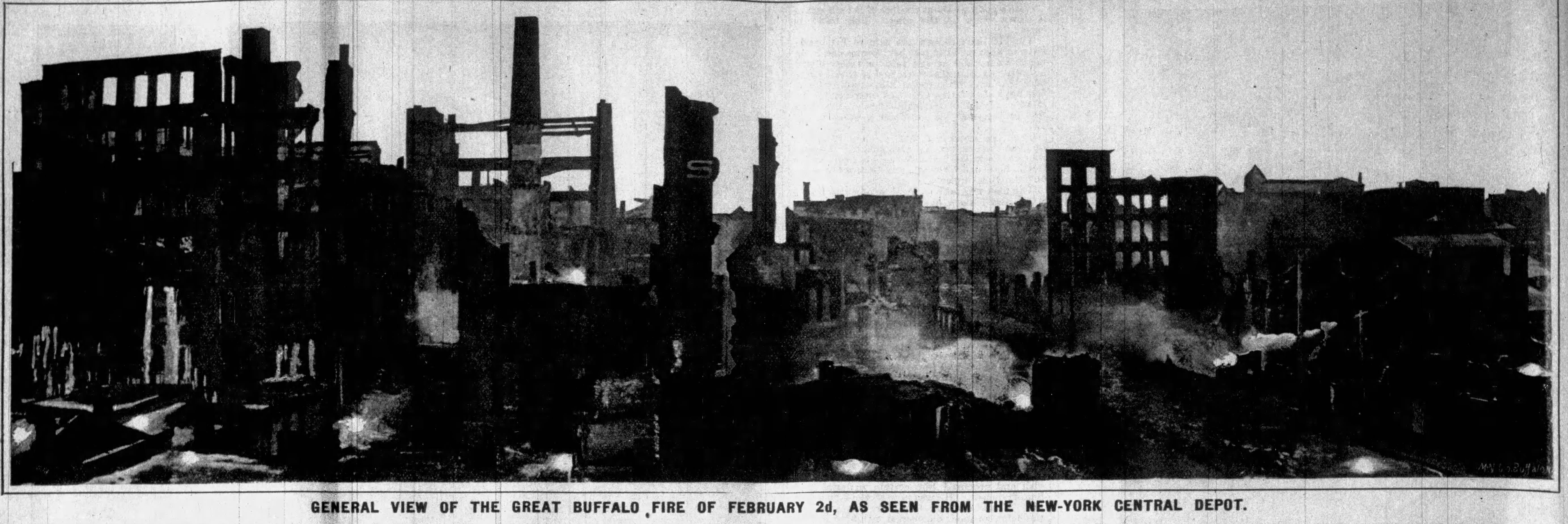

In 1889, Wells Street was the scene of a large fire. The fire was reported as having “no parallel in the history of the Queen City of the Lakes,” measured in magnitude by the area of the burned district, by monetary loss, and by difficulty in slowing the flames. Newspapers reported that the only fire worse was when all of Buffalo was burned to the ground during the War of 1812. The 1889 fire affected Wells Street, Seneca Street, Carroll Street and Exchange Street. This area was a major business center for Buffalo at the time. Due to its location close to the railroad stations, it was a location for several well-known hotels and lodging facilities, as well as industry that used the rail, since it was close to the depots.

Sketch of the Wells Street Fire after Burning for more than 12 hours

The fire broke out at 2:45am on February 2nd, 1889. A night watchman saw flames on the fourth floor of the Root & Keating Building and sounded the alarm. The wind quickly spread the fire to the surrounding buildings. The flames were so high they could reportedly be seen as far away as North Street. Strong winds helped the fire to spread quickly and caused a great deal of destruction. The fire did an estimated $2.0 to $3.0 Million in damage ($68 Million to $102 Million in today’s dollars).

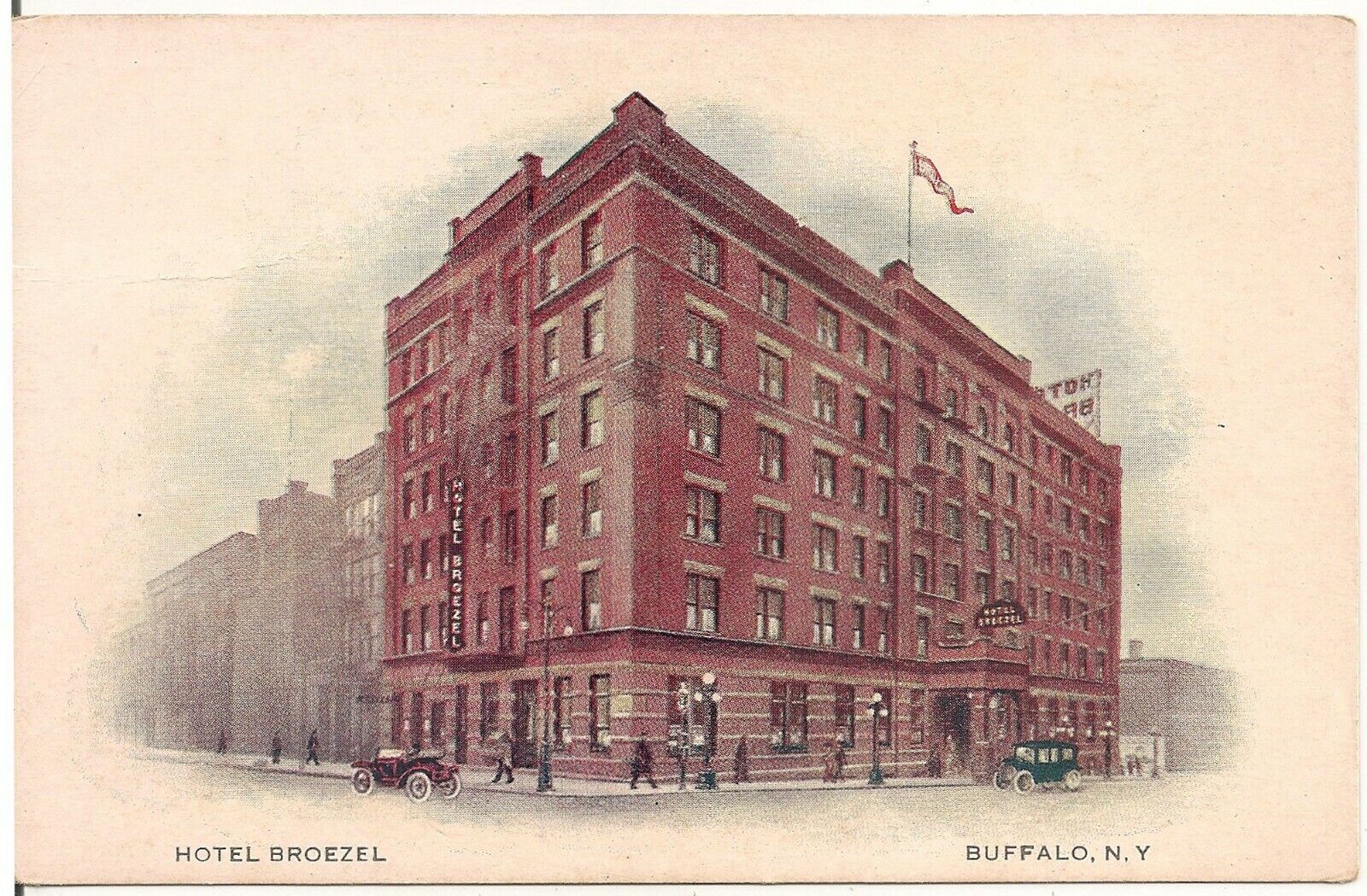

Postcard of Hotel Broezel located at the northeast corner of Wells and Carroll Streets

Guests at the Broezel House and the Arlington, two of the city’s better-known hotels, were able to escape just moments before the hotels went up in flames. Within an hour, all of Wells Street was a mass of flaming ruins.

Forty buildings were damaged by the fire, with many destroyed entirely. The tallest of the burned structures was the seven-story Hoffeld Building on Carroll Street. Most of the buildings in the area were 4 to 5 stories tall. Major Buildings/Businesses that burned included Zingsheim & Wile Clothing, Hoffeld & Co Soap and Leather, Moffatt & Bros Shoe Factory, Goldstein Boots & Shoes, A.T. Herr & Co Liquors, SS Jewett & Co Stoves and Ranges, Swift & Stantback Stoves and Tinwares, Reynolds Boots and Shoes, Campbell Hats and Caps, Sibley & Holmwood Candy Factory, Root & Keating Leather, Dentsch & Schauroth Boots and Shoes Factory, Schantz Button Factory, Hoffeld & Co Leather Belting, Anderson Harness Company, Zimmerman Saloon and Boarding House, Sheehan, French & McCarthy Saloon & Restaurant, Byers Saloon, Arlington Hotel, Grant Coffee & Spice Mill, American Express Supply Department, Broezel House Saloon and Boarding House, Egan Liquors, Ruslander Clothing, Fowler & Son Carriage and Woodwork, Churchill & Sons Groceries, Robertson Hats and Caps, Hearne Confectionary, Deuther Picture Frame Manufacturing Company, Donaldsons Stoves, S. Cohen Hats & Caps, Barmon Dry Goods and Millinery, Pinkel Dye Works, Wechter Furnishings, Brown Fancy Goods and MIllinery, Spencer & Co Tailor and the Wells Street Chapel.

Map of the Burned District of destroyed buildings after the Wells Street Fire. Source: Buffalo Express.

Modern view of the burned district and Wells Street, both shown in red.

News of the fire was reported in newspapers across the country. The fire began to be referred to as “the Great Wells Street Fire” or “the Great Seneca Street Fire.” At least 20 people were injured during the fire – mostly firemen. One fireman, Richard Marion, was trapped under fallen bricks in the Hotel Arlington when it collapsed and lost his life during the fire. It took six hours to dig his body out of the debris. Miraculously, no one else was killed. Fire Chief Fred Hornung’s arm was nearly severed by a falling plate glass window. It was estimated that 1,000 people were put out of work by the fire. It took several weeks to clear the debris and reopen Wells Street after the fire. Some businesses rebuilt, and some decided not to. Hotel Broezel was rebuilt; the Hotel Arlington was not. By August, the Buffalo News reported that the Seneca Street Burnt District was “building up better than ever.” The Buffalo Sunday Morning News reported the day after the fire, “One beauty about Buffalo’s fires is this: there is a phoenix goes with every one of them.”

View after the fire, Feb 10, 1889. Source: Buffalo Courier Express.

The Buffalo Fire Department referred to the Fire Alarm Box 29 at Wells and Seneca Street as the “Hoodoo Box” because it was believed to be cursed. Several fires broke out in the area besides the Great Wells Street Fire of 1889. In 1874, Fireman John D Mitchell was crushed to death by falling bricks at the Red Jacket Hotel fire. In 1880, a fire occurred at the furniture factory on Carroll Street at Wells. In January 1907, a fire started at the 8-story brick Seneca Building at 103-107 Seneca Street. Originally built as a hotel, the building had been converted into offices and a pawnshop. While fighting the fire, a collapsing wall trapped more than 20 firemen. It took hours to rescue them. Three firemen died – Lt William J. Naughton, Stephen E. Meegan and John R. Henky. Another fire in 1913 at Box 29 sent two firemen to the hospital with smoke inhalation. After so many fires at Box 29, the National Board of Fire Underwriters and insurance companies looked into the reason for so many fires in the area. They concluded the fires were only coincidental that their location was so prevalent, determining it was due to the many factories and hazards in the area.

The area around Exchange, Wells, and Carroll Streets began to decline significantly once the NY Central Station on Exchange Street closed in 1929. Exchange Street, once one of the most important thoroughfares, lost most of its businesses and became a ghost town after the railroad moved to Central Terminal in the Broadway Fillmore neighborhood. Despite so many changes to the area by urban renewal projects, the “hoodoo” firebox 29 is still on Seneca Street and can be seen near where the intersection of Wells would have been.

In 1978, Wells Street was acquired by the State of New York for the construction of the Elm Oak Arterial Highway. Wells Street disappeared from Buffalo. The next time you head downtown via Elm Street, you’ll be driving right over where Wells Street once was located. When you take that ramp, think of Chandler Wells and be thankful that he fought for our water system and gave us clean drinking water. And remember the commercial district that once existed there, wiped away by fire, urban renewal, and time.

I’ve scheduled some tours for this summer. You can view the dates at this link: buffalostreets.com/2024/06/27/free-downtown-history-walking-tours-2/

Want to learn about other streets? Check out the Street Index. Don’t forget to subscribe to the page to be notified when new posts are made. You can do so by entering your email address in the box on the upper right-hand side of the home page. You can also follow the blog on Facebook. If you enjoy the blog, please share it with your friends; It really does help!

Sources:

- Smith, H. Katherine. “Wells Street a Mayor’s Memorial.” Buffalo Courier Express. January 15, 1939, p12.

- “Buffalo Juvenile Asylum- Meeting Last Evening.” Buffalo Daily Dispatch. December 27, 1856, p2.

- “Married”. Buffalo Daily Commercial. April 21, 1837, p2.

- “Chandler J. Wells: A Useful Life Ended.” Buffalo News. February 4, 1887, p1.

- “Death of Chandler J. Wells.” Buffalo Times. February 4, 1887, p1.

- Sheldon, Grace Carew. “Wells Earned Title of Reconstruction Mayor by his Deeds in Office.” Buffalo Times. October 5, 1919, p50.

- Burr, Kate. “The Mansion that Housed a President.” Buffalo Times. June 27, 1926, p14.

- “Unequaled: A Great Business Center Burned.” Buffalo Weekly Express. February 7, 1889, p1.

- Ditzel, Paul. “The Hoodoo Box”. Buffalo News. May 15, 1983, p195.

- “Notice of Appropriation of Property”. Buffalo News. June 14, 1978, p67.

- “Buffalo Has A Big Fire.” The New York Times. February 3, 1889, p1.

- “Extra! Fire! The Worst Buffalo Has Ever Had.” Buffalo News. February 2, 1889, p1.

- “Beginning to Clear Up.” Buffalo Courier Express. February 12, 1889, p5.

- “Well It Was Done.” Buffalo Commercial. February 21, 1889, p3.

- “Where the Ruins Were.” Buffalo News. August 13, 1889, p10.

- “Wells Residence Sold.” Buffalo News. February 24, 1893, p13.