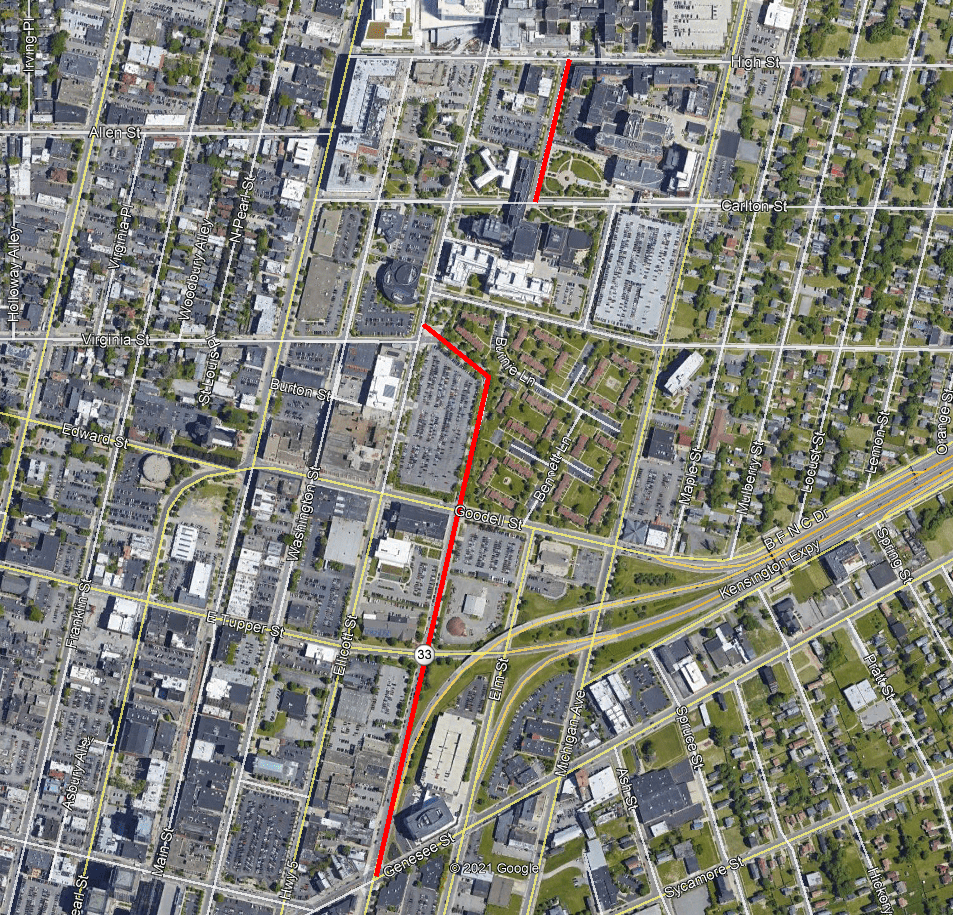

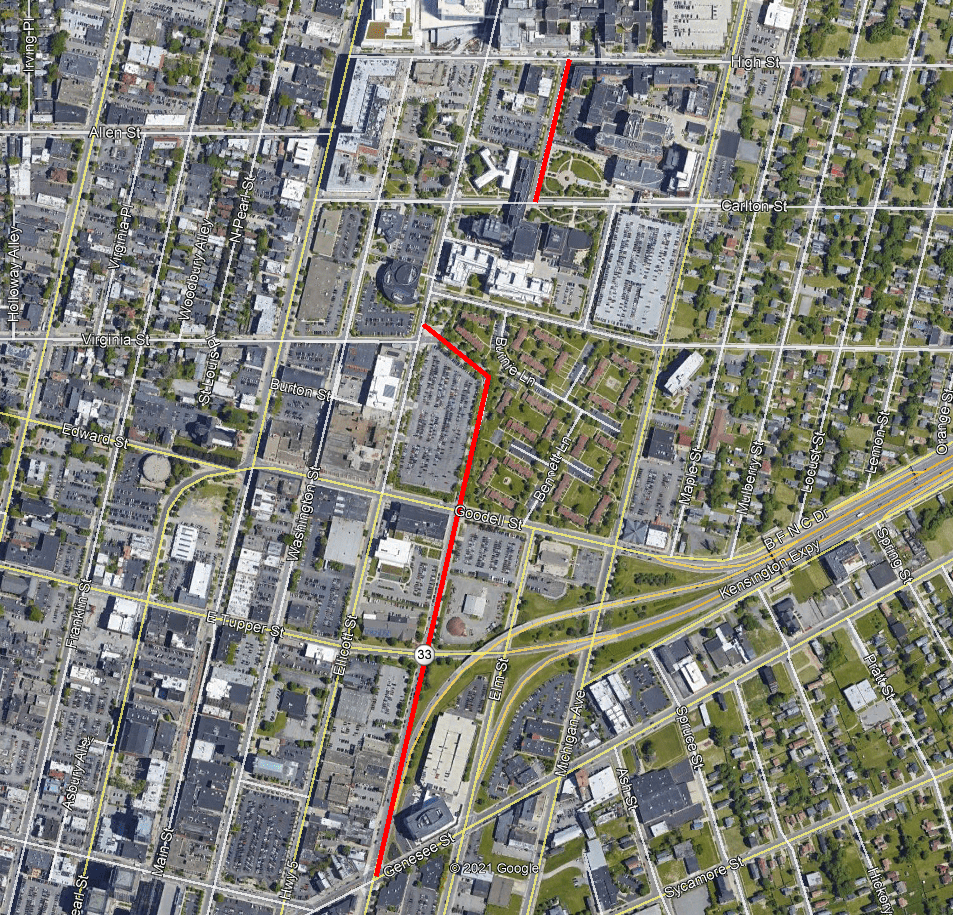

North Oak Street shown in red. Source: Google

Today, we are going to be talking about urban renewal again, specifically what was known as the “Oak Street Redevelopment Project”. The project revolved around the North Oak neighborhood, bounded by Best, Michigan, Goodell, and Main Streets. This is basically the same boundary as the Buffalo Niagara Medical Campus today. North Oak formed the central corridor of the neighborhood. It’s ironic that the street they named the project after was pretty much removed from the area, as Oak Street now runs disjointedly through the medical campus.

North Oak Street runs between Genesee Street and High Street. This is one of the odd street naming conventions in this area. Elm Street and Michigan Avenue remain Elm and Michigan north of Genesee Street, without the north demarcation. There was historically a North Elm Street, running between Northampton and Riley Streets, but it was renamed Holland Place. Similarly, nearby Pine Street north of Broadway becomes North Pine while the other streets in this area do not change as they continue across Broadway. I am not sure of the rationale behind these naming conventions, in the case of North Oak, I imagine it could possibly be to differentiate the residential portion of Oak Street from the business section which runs from Genesee Street to Seneca Street. The southern section of Oak Street has also been changed greatly by urban renewal as well. In a separate urban renewal project, everything between Elm and Oak Streets in downtown was demolished.

Historically, the North Oak area was referred to as “The Orchard and the Hill”. The Orchard is what we would refer to today as the Fruit Belt, with the streets named after fruits. The Fruit Belt term began to be used in the 1950s and 60s. More to come on the Fruit Belt in future posts. The Hill was built around the area that is now Buffalo General Hospital, first built on High Street between North Oak and Ellicott Streets. High Street is the top of the hill, hence its name as the highest street. Due to the hospital, the area is sometimes called “Hospital Hill”. When the hospital first opened in 1858, High Street was a rural area, outside of the city. Keep in mind that when the City limits were set in 1832, North Street and Jefferson Street were set as the outer limits of the City of Buffalo – most of the city was still concentrated between the Terrace and Chippewa Street. This was the northeastern corner of the city limits. Up through the 1860s, much of the area between Mulberry Street and Main Street was open fields. This is where the circus would pitch tents during summers.

The gentle slope of the hill set the area aside from the rest of the East Side. As buildings grew on Jefferson, Genesee, and Main Streets, the neighborhood was hidden from view. The streets had lots of trees and gardens. There weren’t large mansions or estates in the neighborhood, so there was a street face of small frame houses built close to the street line. This created a continuous urban feel to the neighborhood. The area was mostly residential. Many of the first residents came in the 1830s when a group of German Lutherans fled the religious persecution they were experiencing and came to Buffalo to settle in this area. Due to the German’s proclivity towards brewing, the area is also sometimes referred to as “Brewer’s Hill”.

Example of a business in the neighborhood – Wil-Bee Dry Cleaners on Ellicott Street near Best Street, circa 1944. Building was built around 1864. Source: George Apfel, friend of author

The main commercial streets were Virginia, High, and Carlton Streets, which were lined with two and three-story cast iron and brick buildings with stores downstairs and apartments above. Most of the residents lived and worked in the neighborhood – bakers, confectioners, seamstresses, carpenters, blacksmiths, and coopers. Taverns were important institutions and social centers where the neighbors would mingle. There were also many churches in the neighborhood. One of the jokes in the neighborhood was that if you had a nickel, you could have a pint of beer for four cents and still have a penny left for the church offering plate.

By 1894, the neighborhood was mostly built out – mainly with one and a half-story wood-frame houses and two-story commercial buildings. By the 1920s, this was one of the densest areas of the city. Since the area developed as a working-class neighborhood, many of the residents relied on shops and services that were only a short walk away. This was the horse and buggy era, and at that time, those were typically not within the means of a working-class family. The Washington Market at Washington and Chippewa allowed many of the residents access to a variety of fresh produce and products just a short walk away.

North Oak Street was a quiet, tree-lined street. During the 1880s, North Oak was considered the Delaware Avenue of the East Side. There were stately homes with tall windows and formal gardens. Three mayors grew up on the street. Soloman Scheu, Mayor of Buffalo from 1878-80 lived at North Oak and Goodell Street. Mayor Scheu was famous in the neighborhood for the dinners hosted at his home and his New Years Parties were the hit of the neighborhood. After his death, his house was used as the Neighborhood House for many years, one of Buffalo’s earliest settlement houses. The house was torn down to become the M. Wile Company clothing factory. Louis Fuhrmann, Mayor from 1910-17, lived at North Oak near Tupper in a big frame house with massive fireplaces. After he was mayor, he moved to the Wicks House on Jewett Street (across from the Darwin Martin House). Charles E Roesch, Mayor from 1930-33 lived at 633 North Oak. He was born and raised on the street and continued to live there while he was Mayor.

Public School No. 15 was located on North Oak Street, at the corner of Burton Street. The College Crèche, a day nursery was also on North Oak Street. The Crèche served 40 children whose mothers were widowed or deserted. Buffalo General Hospital, the first big hospital built in Buffalo was at North Oak and High Street. In the 1850s and 60s, the Ladies Auxiliary helped fight to get the hospital built. Nearly every society woman in Buffalo was a part of the auxiliary. It was a small feat at first to get the hospital built, but it continued to grow and prosper into the entity that we know today.

There were also many churches in the neighborhood, with two churches on North Oak Street – the Hellenic Eastern Orthodox Church, built like an old Greek Temple was located at 361 North Oak Street. The Hellenic Church eventually moved into the former North Presbyterian Church at Delaware and Utica in December 1952, having outgrown its Oak Street space. St. Mark’s United Evangelical Church was also located on North Oak Street near Tupper Street. In 1929, St. Mark’s merged with St. Paul’s and used their building on Ellicott Street between Tupper and Goodell. The church was demolished as part of the construction of the Oak Street interchange of the Kensington Expressway in 1970.

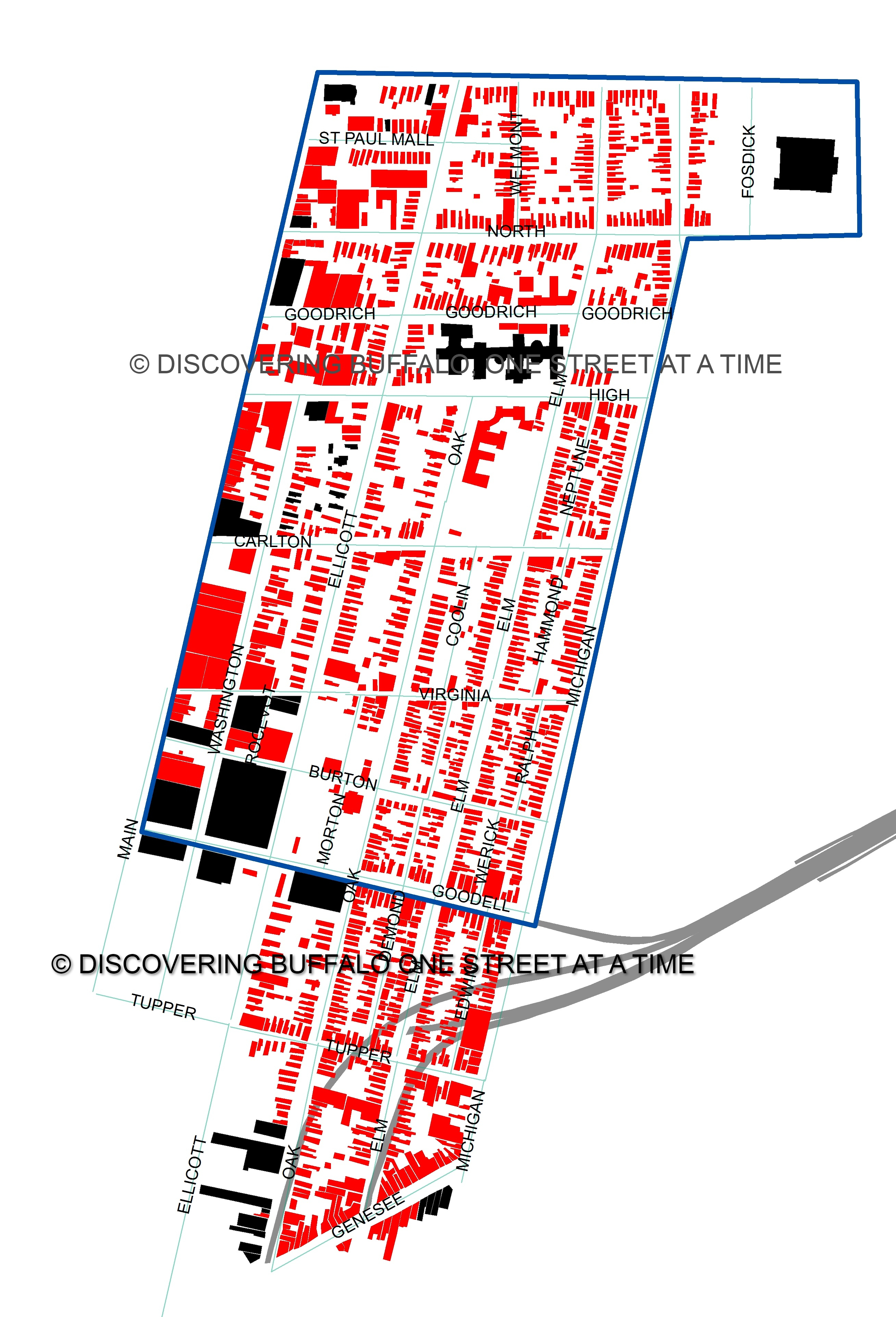

Oak Street Renewal Area shown in blue. Extant streets shown in green. Non Extant Streets shown in red. Source: Author, based on historic maps

Houses on Ralph Street. Source

The North Oak neighborhood was a dense neighborhood. I often get questions from readers researching their family histories. They’ll say, “I found the house was at this address, but I can’t seem to find it on a map”. Usually, it’s because a street name has changed, which we’ve covered a few on this blog. But sometimes, it’s because the street no longer exists. Here are some of the forgotten streets of the North Oak Neighborhood:

- Burton Street- a portion of this still exists, but the road used to reach all the way to Mulberry Street

- Edwin Alley – between Elm and Michigan, running from Goodell to Tupper

- Werrick Alley – between Elm and Michigan, running from Goodell to Burton Alley

- Ralph Alley – between Elm and Michigan, running from Burton to Virginia

- Hammond Alley – between Elm and Michigan, running from Virginia to Carlton

- Demond Alley – between Oak and Elm, running from Tupper to Virginia

- Coolin Alley – between Oak and Elm, running from Virginia to Carlton

- Morton Alley – between Ellicott and Oak, running from Goodell to Virginia

- Neptune Alley – between Elm and Michigan, running from Carlton to High

While in many parts of the city, the Alley name is reserved for the rear part of the property, often for service to a carriage house or garage. However, these alleys in the North Oak Neighborhood were lined with their own rows of houses, due to the density of the neighborhood. Leading to some of the confusion is that some of these alleys had additional names over the years:

- Demond was Boston Alley

- Morton was Weaver Alley

- Edwin was Goodell Alley

- Hammond was Swiveler Alley

- Neptune was Ketchum Alley

- Coolin Alley was also called Codlin or Collin Alley

Example of the type of housing in the North Oak Street neighborhood. Source: New York State Department of Health

The neighborhood continued up through the 1950s when project talks began for the redevelopment of the area. The city applied for funding from the federal government in the late 1950s. This was the City’s fourth federal aid renewal project. The City applied for the funds “with the background of the decade old failure of the Waterfront and Ellicott District renewal projects to materialize and slow pace of developing the Thruway Industrial Park as a renewal project.” The City was slow to move on the Oak Street project, despite announcing plans, leading to many tenants abandoning the area prematurely. This furthered the decline and blight of the neighborhood.

Mayor Frank Sedita signed the contract between the city’s Urban Renewal Agency and the US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) for the 145 acre Oak Street Redevelopment Project Area. The project to acquire and clear the land and build new housing was expected to take five years and a phased approach. They planned to do a “tear down-then building” approach which at the time was referred to as a “checker-board” method of demolition and new construction. The intent was to help minimize the relocation difficulties for residents living in the area. The long-range plan called for 1500 new housing units built over five years. Approximately 514 families and 311 more individuals would be relocated as a result of these activities.

The Oak Street Redevelopment Project was to include

- 1544 low/moderate and elderly housing units

- Recreation facilities

- Spot residential rehabilitation

- Commercial Plazas

- Hospital and Medical Facility Expansions – a $4 Million Roswell Park Research Studies Center, a $4.3 Million Roswell Park Cancer Drug Center, a $4.5 Million Buffalo General Mental Health Center, and a $1.6 Million Buffalo Medical Group building.

- Three new parking ramps – one on Michigan between Carlton and Virginia Streets – to serve Roswell Park Memorial Institute, one at the SW corner of Michigan and North to serve Buffalo General Hospital, and one on Goodell between Oak and Ellicott Streets – to serve the Courier News, Trico, Eastman Machine, M. Wile and other industrial businesses in the area. These new parking ramps would have built 4,100 new spaces. The largest of the three ramps, the 2000 space ramp on Goodell to serve the industrial businesses was never built.

The initial new housing was at the site adjacent to what was then the Fosdick-Masten Vocational School. They purchased 39 parcels and tore down 29 buildings along Michigan between North and Best Streets. In April 1968, the Board of Education agreed to release the open space around the school to BURA for these new apartments. The school had been planning to move to Main and Delevan when their new school was completed. This never happened and Fosdick-Masten graduated its last class in 1979. The school was used as a warehouse and the interior was stripped, with plans to be demolished. Those plans also did not come to fruition. In 1980, the school became home to City Honors School. Along the Michigan Avenue side of the site, they built 160 units of townhouses and garden-style apartments there, called Woodson Gardens. A new street, Fosdick Avenue, was built to serve these apartments. Woodson Gardens were demolished in 2013 and the school is raising money to rebuild their open space into Fosdick Field.

St. Philip’s Episcopal Church, which was located at 161 Goodell Street worked with the city to be the nonprofit sponsor of the first phase of construction activities. St. Philip’s was founded in 1861 in a basement on Elm Street between North and South Division. At the time, they were one of the seven original African American Episcopal churches in the country! St. Philip’s expanded in 1921 when they moved to Goodell Street, to the former home of St. Andrew’s Episcopal Church. The church had been built in 1892. St. Andrew’s moved to Main Street in University Heights. St. Philip’s worked with the city to help relocate the residents into new housing. The church was originally going to be moved to a new site within the neighborhood – to the corner of North and Ellicott Street. Those plans fell through. In 1973, St. Philip’s church was razed by the urban renewal project. The church secretary stated, “We survived as an African American community for more than 150 years. Now we’ve been through trials and tribulations. It wasn’t all pretty and sweet. It’s just the way it was”. The congregation now calls the Delevan-Grider neighborhood their home.

William Gaiter was interviewed in the early 1970s as a leader in the Black Community and was looking forward to seeing the new housing developed in the area. Especially the 500 units of low to moderate-income housing for elderly people that was planned for the site. By 1975, the units had still not been built, due to lack of funds.

Example of some of the run down houses in the North Oak Street neighborhood. Source: New York State Department of Health

The project was originally planned to start in 1962 and be completed by 1965. The Urban Renewal Commissioner, James Kavanaugh, earmarked $599,000 for razing properties before the Common Council and the Federal Government approved the project. This lead to displacement of residents before the relocation study was completed, so they were not eligible to receive their federal grants and assistance with relocating their families, who were made homeless by the urban renewal project. The buildings started to be razed in May of 1965 because Roswell Park Memorial Institute was planning to start their expansion project, so they needed the building site to be clear. Buildings were demolished, even though the federal project wouldn’t be approved until July of that year. In May 1968, the City of Buffalo went to court to obtain titles to 15 of these parcels near Roswell. The owners would be paid 75% of the federally established price for their properties while the properties went through the condemnation process. They had already obtained titled to 20 of the properties in this area.

I was able to speak to the Salvatore Sisters, Melody and Michelle. Their family lived at 605 North Oak Street. The house had been purchased by their parents June and Michael Salvatore in the mid-1950s. The house had been divided into four apartments, they lived in the upper rear apartment. They attended 2nd and 3rd grade at School No 15. They would go to Barone’s corner store at North Oak and Carlton. Like many property owners in the area, the family depended on the rental income. Offers were made to purchase the properties in the area by eminent domain. The City’s offer to buy the house didn’t take into consideration the loss of the rental income in addition to the loss of their property and their home. June Salvatore hired an attorney and sued the city for fair value. In the meantime, houses around them were demolished, one by one. Construction crews would leave debris around their property to intimidate them and block access to their home. In the end, 605 North Oak was the last house standing on the North Oak and Elm Streets. June Salvatore refused to be intimidated by this and continued fighting. The sign went up on their house that said “We would rather fight than submit to legal robbery.” Eventually, June Salvatore won the battle and was given $35,000 for the house (about $240,000 in 2021 dollars). The family moved in 1968.

While June Salvatore won her battle, how many were not so lucky?

Vacant lot in foreground where homes had been demolished. Houses in the rear waiting to be demolished. Source: New York State Department of Health

Demolition of this area around Roswell began in January 1968. There were 126 people living on the block bounded by Oak, Elm, Carlton, and Virginia. There were also commercial properties – businesses on the site included Joseph A Kozy, Volker Brothers Inc, Inro Inc, Pollack Building Corp, and Kreiss Sign Company.

A second area that began to be cleared in 1968 was the 8 blocks that became McCarley Gardens eventually. This area was home to more than 530 people. There were also five commercial properties – the Good Neighbors Store, Nino’s Entrata, W. Martym Cleaner, Mildred’s Food Store, and T&L Cleaners. Two other non-residential properties were in this area – St. Philip’s Episcopal on Goodell Street and Neighborhood House Association on Ralph Street. Neighborhood House was a settlement house founded in 1894. We discussed St. Philip’s above. In 1981, Neighborhood House merged with Westminster Community House to form Buffalo Federation of Neighborhood Centers (BFNC). BFNC Drive, which runs between the Locust Street exit of the Kensington Expressway and Goodell Street, is named after the organization, which provides family focused services for adults and youths living in low income and disadvantaged neighborhoods throughout Buffalo, Niagara Falls and Lockport. The road was previously North Service Drive was renamed after the organization in 1994 as part of their centennial celebrations.

North Oak Street “Wasteland”. Source: Buffalo Courier Express, May 1973

By 1972, only 60% of the area had been demolished when President Nixon put a freeze on federal funds to build low-cost housing. The area was left littered with building debris and rubble. The City had planned to avoid what had happened in the Ellicott District, where the land laid cleared, vacant and strewn with trash for years. Instead, the Oak Street project created an eyesore on the edge of Downtown, right where motorists were exiting the new Kensington Expressway. As motorists drove into Downtown, they were greeted with a view of acres of rubble-strewn land, surrounded by empty, crumbling houses. The City’s Community Development Commissioner’s solution was to screen the view by erecting a fence. The fence held a sign explaining that the clearance activities were a “measure of progress toward making Buffalo a more attractive and livable city”.

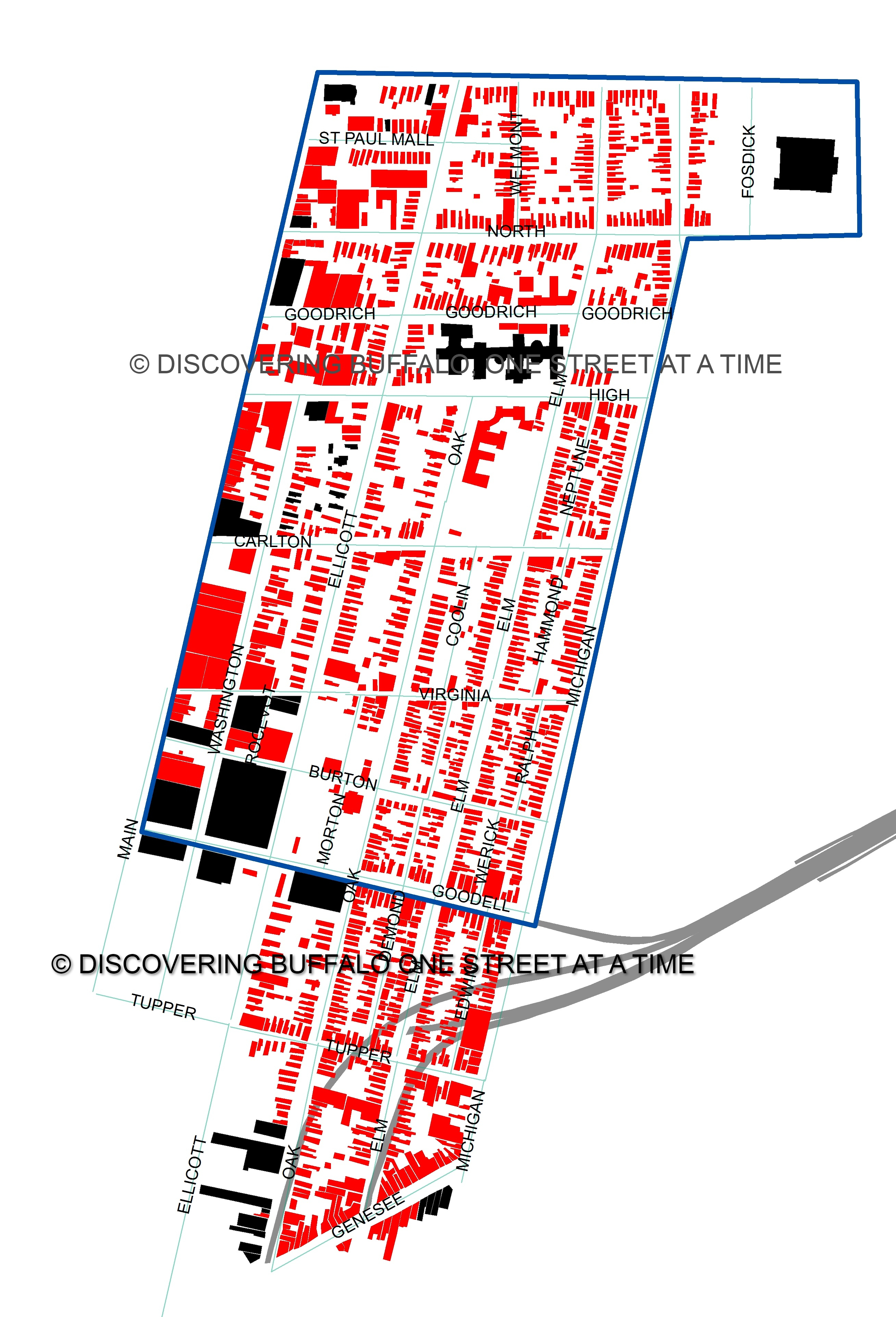

The Oak Street Redevelopment Area outlined in blue. Buildings shown in black are still standing. Buildings in red have been demolished. Source: Author, based on 1951 Sanborn Maps

In 1951, the Oak Street Redevelopment Area was home to 1308 buildings. Only 41 of those buildings remain standing today. Of the 1268 buildings demolished, 461 were residential: 434 frame houses, 1 rooming house, 13 flats (Buffalo upper and lowers), and 13 apartment buildings. As was the case with the Salvatore home, many of the houses had been subdivided into multiple units. The average number of people per unit in this neighborhood was 2.93 people. Conservatively, this neighborhood had been home to at least 2000 people, and likely many more. The 1500 housing units that were planned for the redevelopment area resulted in only 513 being built….with most of those units built nearly two decades after the residents were kicked out of their homes and the buildings demolished.

Roosevelt Apartments, 1978Source

In 1971, the City unveiled plans for its first big modernization project. This was 80 apartments designed for the elderly at the building at 11-23 High Street, the Roosevelt Apartments. The building is a seven-story Renaissance Revival Style building that was built in 1914. The city acquired the building as part of the Oak Street Redevelopment. This was the first project of its kind undertaken by BURA. The current rents in the building were about $63 and they were expected to go up to $79/month ($520 in 2021 dollars) for one-bedroom and efficiency apartment. The project never happened and the city turned out all remaining tenants in 1973 because they were losing money on the building. the building sat vacant, on the brink between demolition and revitalization. Groups went back and forth trying to figure out a way to renovate the building and find financing. The building was slated to be torn down if one of the interested groups, Roosevelt Renaissance Group, was unable to obtain financing for their project. The building sat vacant and abandoned until 1984 when it was converted into 113 apartments subsidized for the elderly. The apartments are currently managed by MJ Peterson.

After years of sitting vacant and being an eyesore at the edge of Downtown, McCarley Gardens was built. The complex consists of 150 affordable apartments, with rents subsidized by HUD. The groundbreaking for McCarley Gardens was in December 1977. The site was built by and is still owned by, Oak-Michigan Development Corporation, an affiliate of St. John Baptist Church, located just across Michigan Ave from the complex. The 15-acre housing site is located between Goodell, Oak, Michigan, and Virginia Streets. They were the first low to moderate-income housing built in Buffalo in a decade and they received more than 1000 applications for the 150 units before opening. The first tenants moved into the complex in March 1979 and the site was formally dedicated in July of that year. McCarley Gardens is named after Burnie McCarley, a pastor of St. John’s. Burnie’s daughter Jennie married King Peterson, for whom King Peterson Road is named.

When McCarley Gardens opened, they were touted by the Courier Express as an “outstanding example of what can be accomplished through private initiative” and that St. John Baptist should be “highly commended for pursuing the project over mountains of red tape and craters of bureaucracy to a successful completion”. The project took nine years to be completed. The hope was that McCarley Gardens would serve as a rebirth for the neighborhood.

UB Medical School, Main and Allen Source

In the early 2000s, University of Buffalo proposed removing McCarley Gardens to turn the site into an academic and research facility to support the Buffalo Niagara Medical Campus. The plan was vehemently opposed by both residents and politicians. By 2014, UB backed away from those plans, building their new Medical School at Main and Allen Street and using the former M. Wile Company space as the UB Downtown Gateway Building. Several different plans have been made for rehabilitation of the McCarley Gardens complex in recent years, including a recent plan involving Nick Sinatra to rehab many of the units to bring them up to date.

The other housing built in the Oak Street Redevelopment Area was Pilgrim Village, an 11.3-acre site at the north end of the redevelopment area, bounded by Michigan, Best, North, and Ellicott Streets. The 90-unit affordable housing community was built by former Buffalo City Court Judge Wilbur Trammell in 1980. In 2002, the site was passed to Trammell’s son, Mark. Mark Trammell worked with McGuire Development in 2017 on a redevelopment project for the site that was called Campus Square. At that time, 25 apartments were demolished to prepare for new buildings. Campus Square was supposed to be the start of redevelopment for the entire site, but construction was delayed, the project stalled and McGuire ended up taking the whole Pilgrim Village site through foreclosure.

A portion of the Pilgrim Village site, 4.5 acres at the corner of Michigan and Best, was purchased by SAA-EVI, out of Miami. The group is planning a $50 Million project to build two affordable housing projects – a four-story building for seniors and a five-story building for families. The two buildings are planned to have 230 apartments in total. Plans for the rest of the Pilgrim Village site include new buildings that are a mix of housing, offices, stores, and medical labs. The blocks have been difficult to redevelop despite many efforts over the years, so it is yet to be seen what will happen at the site. There are currently 65 townhomes spread across the site.

Washington Place Houses that were preserved in the 1980s. Photo by Author

Four houses that were supposed to be demolished were saved. In the early 1980s, these four houses on Washington Street were boarded up, vandalized and filled with trash. They are brick, Italianate houses built before 1872 and are adjacent to four houses on Ellicott Street used by St. Jude Christian Center and the Kevin Guest House. The City was looking to demolish the Washington Street homes at 923, 929, 933 and 937 Washington Street to clear the land for a future, undetermined development. These houses were the last of their kind in this area and the only remaining homes on Washington Street. Austin Fox, a preservationist and architecture buff stood up to the City and argued the case for the houses. The restoration project that resulted was called Washington Place. The project restored the exterior of the buildings with public money with the intent of selling them to private developers. The City spent $330,000 in Community Development Block Grant money to clean the outside brick, repair the masonry and put on new roofs, gutters, downspouts, doors and porches. The street on this block had been cobblestone, but the city repaved the street and built a 40-car parking lot adjacent to the buildings to make them more attractive for tenants. At the time, this was one of four city-managed projects happening in this neighborhood that were designed to bring new life to the area. The other projects were the Allen Street subway station along with the metro rail, the renovations of the Roosevelt Apartments, the construction of the 14-story building at Ellicott and High Streets to expand Buffalo General Hospital, and construction of an indoor shopping mall at Franklin and Allen Streets – can you imagine, a MALL IN ALLENTOWN???? Thankfully, the mall never happened, though the other projects were completed! With the hospital just two blocks away from Washington Place, the houses were marketed for medical offices. As construction was wrapping up in 1981, the City was in negotiations with a medical group to buy the properties. Since 2005, the houses have been owned by an entity of the Buffalo Niagara Medical Campus.

Anchor Bar. Source: Buffalo & Erie County Public Library

One beloved Buffalo site – the Anchor Bar – was among buildings planned to be razed as part of the Oak Street Redevelopment project. The Anchor Bar property was a part of a 3.1 acre parcel that was intended to be redeveloped with housing with St. Philip’s Church located at the NW corner of Ellicott and North Street, as mentioned previously. Those plans did not come to fruition, and in 1974, BURA then intended to build a new facility for Carlton House Nursing Home on the site. The Nursing Home began operating at 60 Carlton Street in the late 1960s, but their original site was purchased by the State for Roswell Park Memorial Institute. Roswell still uses the Carlton House name for the structure. Many in government were angered by the purchase, as the City of Buffalo needed nursing home beds more than they needed the hospital. The Anchor Bar was left out of the nursing home site at Ellicott and North, under the condition that the restaurant be rehabilitated and that the restaurant purchase 16,000 square feet of adjacent property around their restaurant to allow for off street parking lots. The nursing home site at Ellicott and North has been the home of Buffalo Hearing and Speech since their building was constructed in 1994. Can you imagine Buffalo if the Anchor Bar had been demolished just ten years after they “invented” chicken wings? They may not be everyone’s favorite wings, but they certainly are a Buffalo tradition….if they had gone away, would Buffalo be known for wings today, or would everywhere call them chicken wings instead of Buffalo wings?

So the next time you are on the Medical Campus, think back and remember the North Oak Street neighborhood that used to be there. To learn more about how urban renewal shaped the near east side’s Ellicott Neighborhood, you can read this post: JFK Park, A Case Study in Urban Renewal. Want to learn about other streets? Check out the Street Index. Don’t forget to subscribe to the page to be notified when new posts are made. You can do so by entering your email address in the box on the upper right hand side of the home page. You can also follow the blog on facebook. If you enjoy the blog, please be sure to share it with your friends.

Sources:

- Oak Street Project Contract Signed – Courier Express December, 16, 1970, pg 14

- Report on Third Acquisitional Area – Health Research Incorporated New York State Department of Health.

- Report on Second Acquisitional Area. Health Research Incorporated New York State Dept of Health. Roswell Park Memorial Institute. 1968

- Cichon, Steve. “Torn Down Tuesday: Ralph Street has Been Wiped Off the Map”. Buffalo News. November 3, 2015.

- “City Goes to Court over Land Acquisition”. Buffalo Courier Express March 1, 1968

- McAvey, Jim. 3 Auto Ramps Planned for Oak Street Area. Buffalo Courier Express. June 29, 1967.

- Turner, Douglass and Dominick Merle. Commitment of $599,000 Asked of City. Courier Express. September 18, 1961 p1.

- “Council Votes Cash for Oak Street Project” Courier Express, May 18, 1966.

- Locke, Henry. “A Conversation with William L Gaiter”. Buffalo Courier-Express, July 14, 1975. P 9

- Oak Street Area Project Is Backed. Buffalo Courier Express. November 22, 1957. P5.

- Oak St Project Hearing Is Urged – Buffalo Courier Express, Sept 21, 1965, p 4.

- Turner, Douglass and Dominick Merle. Commitment of $599,000 Asked of City. Courier Express. September 18, 1965. P1.

- Dearlove, Ray. McCarley Gardens Keeps Construction on Schedule. Courier Express. August 20, 1989, sect H, p1

- Williams, Michelle. Church Dedicates Pastor’s Dream. Buffalo Courier Express, July 16, 1979, p2.

- City Aides Back Roosevelt Group for Renovation. Buffalo Courier Express. October 25, 1973.

- Epstein, Jonathan. At Medical Campus’ edge, a taller plan for a hard-to-develop block. Buffalo News. July 20, 2020.

- Decrease is Reported in Oversized Classes. Buffalo Courier Express. April 25, 1968.

- “Yes, Mayors Grow on North Oak Street: Three Sons of Tree Lined Thoroughfare have Answered to ‘His Honor’ as Buffalo’s Chief Executive”. Buffalo Timers, Sept 3, 1930.

- Ritz, Joseph. “Oak St Wasteland Seems Likely to Continue”. Courier Express. May 6, 1973, p B1.

- “Planning Board Approve Site for Nursing Home” Buffalo Courier Express. Sept 27, 1974, p 15.

- Cardinale, Anthony and Mark Pollio. “Community Group to Celebrate Centennial Buffalo Federation of Neighborhood Centers Festival Set for Aug 20”. Buffalo News. August 8, 1994.

Read Full Post »

On November 7, 1819, Cicero Hamlin was born in Hillsdale in Columbia County, New York. His parents were Reverend Jabez and Esther Stow Hamlin. Cicero Hamlin would say that he started his life as a poor child and that his only heritage was “being of sound health and good digestion.” Cicero was the youngest of a family of ten. Cicero came to East Aurora in 1836 and purchased the general store operated by his brother John W. Hamlin. The store was located on Main Street near what is now Hamlin Avenue in East Aurora.

On November 7, 1819, Cicero Hamlin was born in Hillsdale in Columbia County, New York. His parents were Reverend Jabez and Esther Stow Hamlin. Cicero Hamlin would say that he started his life as a poor child and that his only heritage was “being of sound health and good digestion.” Cicero was the youngest of a family of ten. Cicero came to East Aurora in 1836 and purchased the general store operated by his brother John W. Hamlin. The store was located on Main Street near what is now Hamlin Avenue in East Aurora.

John Lyth was born in Stockton-Upon-Tees in England in September 1820. Mary Ann Harwood Lyth was born in England in 1817. At age 13, Mr. Lyth learned the trade of earthenware manufacturer. John and Mary Ann were married in 1843. They had three children while living in England – Alfred, John, and Mary. They emigrated to Buffalo in 1850 and had two more children – William and Francis- born here in Buffalo.

John Lyth was born in Stockton-Upon-Tees in England in September 1820. Mary Ann Harwood Lyth was born in England in 1817. At age 13, Mr. Lyth learned the trade of earthenware manufacturer. John and Mary Ann were married in 1843. They had three children while living in England – Alfred, John, and Mary. They emigrated to Buffalo in 1850 and had two more children – William and Francis- born here in Buffalo.

Carlton Street runs from Main to Genesee Street in the Medical Campus and Fruit Belt neighborhoods of Buffalo. Like many streets in this area, it was impacted by the construction of the Kensington Expressway (NYS Route 33), which separates Carlton Street into two, with its final two blocks of the 33, cut off from the rest of the street west of the 33.

Carlton Street runs from Main to Genesee Street in the Medical Campus and Fruit Belt neighborhoods of Buffalo. Like many streets in this area, it was impacted by the construction of the Kensington Expressway (NYS Route 33), which separates Carlton Street into two, with its final two blocks of the 33, cut off from the rest of the street west of the 33. Eben Sprague attended Phillips Exeter Academy and graduated from Harvard College in 1843. After graduation, he studied law in the office of Millard Fillmore and Solomon G. Haven, two of the most distinguished lawyers of their day. Mr. Sprague was admitted to the bar in October 1846. He was a successful lawyer and was associated with both Millard Fillmore and his son, Millard Powers Fillmore. Mr. Sprague founded the firm Moot, Sprague, Marcy and Gulick. He was well respected among the legal community for nearly 50 years.

Eben Sprague attended Phillips Exeter Academy and graduated from Harvard College in 1843. After graduation, he studied law in the office of Millard Fillmore and Solomon G. Haven, two of the most distinguished lawyers of their day. Mr. Sprague was admitted to the bar in October 1846. He was a successful lawyer and was associated with both Millard Fillmore and his son, Millard Powers Fillmore. Mr. Sprague founded the firm Moot, Sprague, Marcy and Gulick. He was well respected among the legal community for nearly 50 years.

Mr. Sprague died on February 14, 1895 at the age of 73. He suffered fell into a coma while home reading to his wife by the fire. He died the next day of kidney disease. His grave says: Jurisconsultus Insignis – Civis Fidelis Literis Perdoctus- Hominum Amator, which means “Distinguished Lawyer – A Loyal Citizen – Lover of Human Learning. He left behind an estate valued at $50,000 in real estate and $150,000 in personal property ($1.6 Million and $4.9 Million in today’s dollars). Eben left his law office to his son Henry, who continued the practice until his death. The firm then continued under Eben’s grandson!

Mr. Sprague died on February 14, 1895 at the age of 73. He suffered fell into a coma while home reading to his wife by the fire. He died the next day of kidney disease. His grave says: Jurisconsultus Insignis – Civis Fidelis Literis Perdoctus- Hominum Amator, which means “Distinguished Lawyer – A Loyal Citizen – Lover of Human Learning. He left behind an estate valued at $50,000 in real estate and $150,000 in personal property ($1.6 Million and $4.9 Million in today’s dollars). Eben left his law office to his son Henry, who continued the practice until his death. The firm then continued under Eben’s grandson! Metcalfe Street runs between Clinton Street and William Street in the Seneca-Babcock neighborhood of the East Side. The street is near the former Buffalo Stockyards and is named for James Metcalfe, a meatpacker.

Metcalfe Street runs between Clinton Street and William Street in the Seneca-Babcock neighborhood of the East Side. The street is near the former Buffalo Stockyards and is named for James Metcalfe, a meatpacker.

Mr. Box retired in 1901. He passed away in 1909 at Saranac Lake. He had suffered from tuberculosis for five years before his death. He spent his last year in the Adirondacks to help with his health. He is buried in Forest Lawn in the Peabody-Selkirk-Box family plot.

Mr. Box retired in 1901. He passed away in 1909 at Saranac Lake. He had suffered from tuberculosis for five years before his death. He spent his last year in the Adirondacks to help with his health. He is buried in Forest Lawn in the Peabody-Selkirk-Box family plot. Shumway Street is a north-south street running between Broadway and Howard Street in the Emslie Neighborhood on the East Side of Buffalo.

Shumway Street is a north-south street running between Broadway and Howard Street in the Emslie Neighborhood on the East Side of Buffalo.

He was also committed to helping Buffalo develop. He helped many Buffalonians establish their large estates as their lawyer, as he was so well trusted in the community that people felt he would help ensure estates were handled in the appropriate manner. Horatio Shumway died in July 1871. He is buried with his wife in Forest Lawn Cemetery. His tombstone says “faithful to every trust”.

He was also committed to helping Buffalo develop. He helped many Buffalonians establish their large estates as their lawyer, as he was so well trusted in the community that people felt he would help ensure estates were handled in the appropriate manner. Horatio Shumway died in July 1871. He is buried with his wife in Forest Lawn Cemetery. His tombstone says “faithful to every trust”.

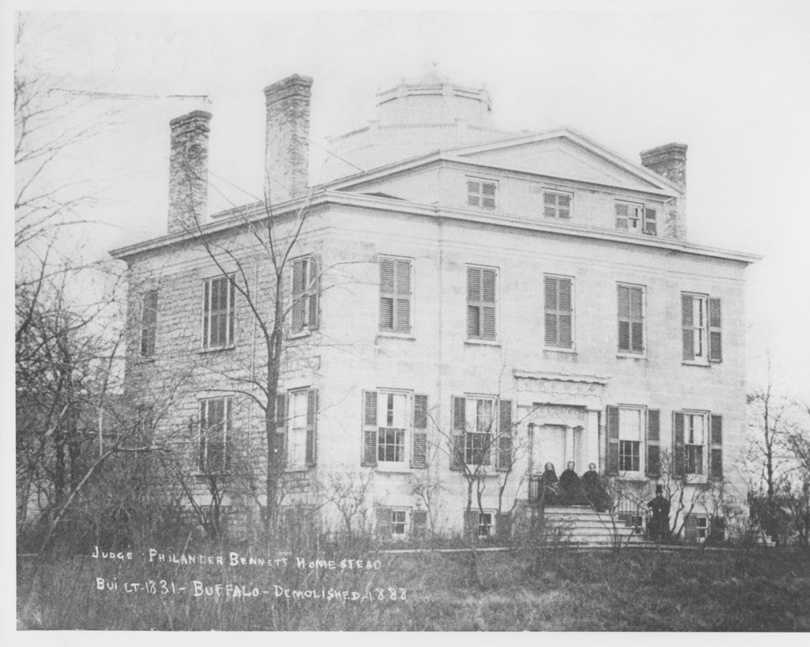

Philander Bennett was born to Nathaniel and Sarah Bennett on April 29, 1795. in Catskill, New York. The family moved to Clinton in Oneida County while Philander was a child. He attended Hamilton College and graduated in 1816. Following his graduation, he went to Delaware, Ohio to try to establish a business. A stock of goods being shipped along Lake Erie had to stop in Buffalo because of a storm. They decided to unload the product in Buffalo and open a business at the corner of Main and Eagle Street, called Scribner & Bennett. Scribner & Bennett quickly became the largest mercantile shop west of Albany.

Philander Bennett was born to Nathaniel and Sarah Bennett on April 29, 1795. in Catskill, New York. The family moved to Clinton in Oneida County while Philander was a child. He attended Hamilton College and graduated in 1816. Following his graduation, he went to Delaware, Ohio to try to establish a business. A stock of goods being shipped along Lake Erie had to stop in Buffalo because of a storm. They decided to unload the product in Buffalo and open a business at the corner of Main and Eagle Street, called Scribner & Bennett. Scribner & Bennett quickly became the largest mercantile shop west of Albany.