Today, we are going to talk about three streets in the Lakeview Neighborhood of the Lower West Side – two of which are named after women! Bonus women’s content: we’ll also discuss a prison designed by a female architect! Today’s post is a partnership with the Buffalo Women’s Caucus for Women’s History Month. Buffalo Women’s Caucus is an organization to empower women in all fields to become leaders and changemakers. You can follow the Buffalo Women’s Caucus by clicking this link: https://www.instagram.com/buffalowomenscaucus/ Today (March 8th) is International Women’s Day, a global holiday celebrating the social, economic, cultural and political achievements of women.

The former location of Root Street shown in Yellow, directly between Rosetta Petruzzi Way and Sally Mae Cunningham Drive. The former Erie County Penitentiary Street, shown in Orange.

Root Street was a short street that ran one block between the Erie Canal and Fifth Street. Fifth Street is now Trenton Avenue. Root Street is no longer extant; it was removed during the construction of the Lakeview Projects.

Root Street was replaced by two new streets in the vicinity of where the street once was – Rosetta Petruzzi Way and Sally Mae Cunningham Drive, named after two women who lived in the neighborhood.

John Root was born in Southwick, Massachusetts, in 1773. He practiced law in Delaware County, New York, for about ten years and then came to Buffalo around 1810. When Mr. Root arrived in Buffalo, the lawyers in Buffalo were Ebenezer Walden, Jonas Harrison, and Heman B. Potter. Potter Street between Broadway and William Street was named for Mr. Potter, but has been replaced by Nash Street. Mr. Root’s first law office was at Washington and Exchange Streets, and he lived at Washington and Swan Streets.

Mr. Root married Christiana Merrill in May 1798. When they first arrived in Buffalo, the Roots shared their home with Christiana’s brother, Frederick W. Merrill and sister, Mary Merrill. Mary Merrill is the woman who is thought to have broken the heart of Seth Grosvenor, causing him to leave Buffalo. Christiana Root died in 1821. Mr. Root married Elizabeth Stewart in 1824. While married twice, John Root had no children.

John Root was considered a brilliant lawyer and orator and was known around town as “Counselor Root.” He was considered well-read in law and equity. Counselor Root practiced in Buffalo for about 30 years before retiring to a lakeshore farm in Hamburg. During his retirement, he provided advice to many young lawyers who’d come to visit him for consultations. He died at his farm in September 1846 at the age of 76. When he died, he was the oldest member of the Erie County bar. He is buried at the Lakeside Cemetery in Hamburg.

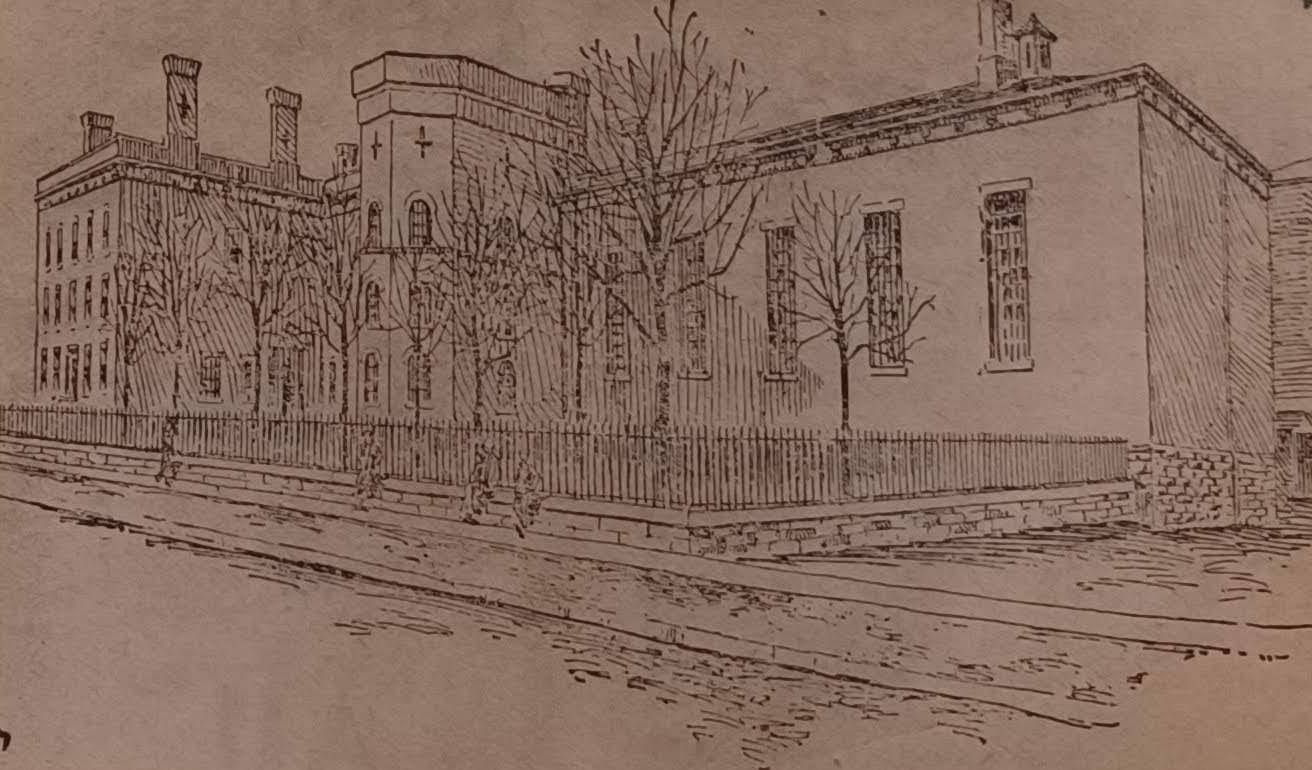

Sketch of Erie County Penitentiary. Source: Courier Express, June 1894.

In 1847, Root Street became the home of the Erie County Work House. This was designed as a workhouse for prisoners under sentence for minor offenses for whom there was neither room nor labor at the jail and whom it was not desirable to send to a State Prison. The stone building was located between Pennsylvania and Root Streets on Fifth Street. In 1851, the Work House name was changed to Erie County Penitentiary. In 1892, the Pen, as it was known, served an average of 416 prisoners “for the reformation of convicts, not younger than 16 years”. Most men committed to the Pen were “tramps” sent to the Pen for short sentences. Superintendent of the Pen, Alfred Neal, was quoted in 1894 saying that “committing tramps and disorderliness for such brief sentences is a travesty of justice” and that “it wipes out their self-respect and creates a feeling of contempt and anger towards more crime.” Quite progressive for that time!

View of the Women’s Cells with two matrons. The space was designed by Louise Bethune. Source: Buffalo News, March 1903.

In 1890, a women’s wing was added to the Erie County Penitentiary. It was designed by Louise Bethune, the first female architect. She was tasked with developing a new type of structure – the County had opted to update the entire facility with heat and water. Louise had been doing landmark work with property sanitation in public school buildings, making her an expert in creating safe and functional spaces.

The Pen was home to some famous guests! After assassinating President McKinley, Leon Czolgosz was first held at Police Headquarters. A crowd of several thousand people gathered, calling for a lynching. Police took Czolgosz away, spreading a rumor that they were taking him to a different city. They ended up bringing him to the Women’s Wing of the Penitentiary and keeping him in the dungeon. Another famous Pen resident was Jack London, the author, who spent 30 days at the Pen in 1900 for vagrancy.

1899 Sanborn Map showing the Erie County Penitentiary Site.

By 1903, the Pen no longer took on long-term sentences and was more of a home for petit thieves, habitual drunkards and “unfortunate women” than a place for genuine criminals. For some, it was a better home than on the streets. They had better food and a warm place to sleep. Around the same time, some people wanted to turn the Pen property over to the State to build a Prison and a new Penitentiary at the Erie County Almshouse site (where UB South Campus is now). At the time, the Pen saw about 4,000 to 5,000 persons received and discharged annually (sometimes the same person multiple times). The Head Keeper at the time described the Pen as not so much a prison but a boarding school for the “discipline of adults.”

Starting in the early 1900s, the county would use land in Alden, the Wende Farm, to use farm prison labor to feed the inmates at the Penitentiary. The land had been donated by Otto Wende to the County. The Work House/Penitentiary was located on the west side from 1847 until 1923, when they moved to a new facility at the Wende farm in Alden. The new facility was designed by William Beardsley, a noted prison architect, and built using inmate labor. The new facility opened on July 12, 1923. The city Penitentiary site was considered a “dungeon” compared to the 800-acre farm in Wende. Farm labor was considered appropriate for inmates, and the farm helped the County financially sustain the prison. The county-run farm had 40 Holstein cows, 200 pigs, and up to 12,000 chickens. Up to 80 inmate farm workers tended to the farm. Chicken raising was the first to go, then cows, but the pigs were still on the farm until 1984. The Erie County farm was one of the last county penitentiary farms in the state – the only other was in Nassau County. The State converted the Wende facility into a state-owned and operated correctional facility in 1983. The County then built a new facility at the site for a new Erie County Correctional Facility. The farm was also home to the Erie County Home and Infirmary, which moved to the site in 1928 and closed in 2005.

Children playing on the grounds of the abandoned Penitentiary. Source: Buffalo Courier, October 1929.

Once the inmates moved to Wende, some people, including the Penitentiary Board, hoped the Federal Government might want to buy the Root Street site for federal use. In 1925, the Acting Superintendent of United States Prisons, HC Heckman, had a press conference with Congressman James M. Mead to state that the federal government was not interested and probably never would be in the property. In 1926, the abandoned Erie County Penitentiary was recommended for purchase by the City. At this time, the City was working on building City Hall and moving out of the combined City-County Hall on Franklin Street (now referred to as Old County Hall). In 1929, the City would receive its share of the City-County Hall building value when the County took it over. The City’s share was set at $862,500. The old penitentiary site was 5.5 acres in size and valued at $225,000. The City considered turning the site into a playground, park or public stadium. The neighborhood around the old penitentiary was thickly populated and could benefit from some public recreation space.

Birdseye View of the Lakeview Housing Project. Rendering by Green & James. Source: Buffalo Courier Express, June 1938.

In 1938, the Lakeview Housing Project began construction on the site as a US Housing Authority project, part of the New Deal program. The project cost $5,000,000 to complete. It was one of the largest construction projects in Buffalo since the Great Depression began. The construction industry was excited to bid on the project, bringing thousands of man-hours of labor and a huge demand for material supplies. The project called for 350 tons of structural steel, 1200 tons of reinforcing, 250 tons of steel joists, 240 tons of steel roofing and 100 tons of steel window frames – a total of 2,140 tons of steel! Not to mention other building materials like cement, brick, lumber, paint, glass, nails, plumbing, etc. Lakeview Project was designed by architects Green & James, who also designed the Commodore Perry Homes, Lasalle and Langfield Projects. The Lakeview Housing was bounded by Jersey, Hudson, Lakeview, Trenton and the Erie Canal.

A 1995 Aerial Photo shows the Lakeview Housing Project outlined in Blue. Note that the Thruway I-190 runs over the former Erie Canal bed.

During the construction of the Lakeview Housing Project, John W Cowper Company, a Buffalo-based contractor, developed a concrete handling method. Their method allowed an entire concrete floor to be poured to cover thousands of square feet in a single day. The method was then used again on the Commodore Perry and Dante Place projects by the company here in Buffalo. By the 1950s, the method was used by most big contractors across the country. The old method involved loading concrete at ground level into two-wheel buggies, raising it on elevators to the construction floor, dumping and sending the buggy down the elevator empty. The new method brings the concrete in the mixer truck, dumping it into crane buckets that can carry 2 cubic yards of concrete each. The new method involved significant time and cost savings for construction projects!

The Erie Canal, forming the southwestern boundary of the Lakeview Housing site, was filled in to build Perry Boulevard, which is now the Niagara Section of the New York State Thruway. The Lakeview Project included 668 units but was increased to 1,028 by the end of 1939. Families began moving into the projects in July 1939.

By the mid-1950s, the Lakeview Housing Project was considered dangerous. The closeness of the projects to the Thruway meant that if there were an accident, a car could crash into one of the homes. Perry Boulevard running through the complex was so narrow that cars had to hop curbs when two cars needed to pass each other. The highway noise and the railroad noise made it impossible to sleep in the uninsulated houses.

By the 1960s, the area was home to fights and issues. Unemployment was an issue across the City of Buffalo as deindustrialization began to take effect, and thousands of Buffalonians were laid off from the steel mills. Unemployment impacts were much greater in the Black Community. Police misconduct was a major source of racial tension in Buffalo. On June 26, 1967, two white police officers intervened in a small fight between two Black teenagers in the Lakeview Projects. It quickly escalated into violence. The next night, approximately 200 people, many residents of Lakeview, responded to the excessive force with demonstrations. The protests that ensued were in response to the many issues facing the Black community at the time – substandard housing, public school education, unemployment and lack of neighborhood investment. The action spread across the East Side, continuing until July 1st. The five-night riot resulted in sixty injuries, over 180 arrests and approximately $250,000 worth of property damage to stores and homes. The Buffalo riot was part of a wave of riots that swept across urban areas of the North in the late 1960s. The Black Community today continues to fight for many of the same things that caused the riots back then, as was seen during the 2020 protests after the death of George Floyd.

Now, on to the women – Rosetta Petruzzi Way and Sally Mae Cunningham Drive! These two streets are named after women who were instrumental in the Lakeview Housing complex over the years.

Sally Mae Cunningham’s gravestone, Concordia Cemetery

Sally Mae Cunningham was a long-time resident of the Lakeview Housing complex. She was known by her neighbors as “the mother of the West Side.” Sally Mae was born in 1914 and grew up in Anniston, Alabama. When she was ten, her stepfather had defied a white shop owner who refused to sell to Black customers. That night, her house was visited by the local Ku Klux Klan. Her grandfather stood up to the Klansmen, unmasked one of them, called him by name and told them to leave. Mrs. Cunningham would later say that memory gave her strength throughout the rest of her life.

In 1952, Mrs. Cunningham and her three children became the first Black family to move into the Lakeview Projects. She was greeted by her neighbors by trash thrown on the lawn and a brick through her window. Sally Mae was quoted in the Buffalo News as saying, “I was threatened lots of times, but I was never afraid.” She was said to have countered the hostility and suspicion with kindness and was able to win over the neighbors and make many friends.

Mrs. Cunningham lived at 971 Perry Blvd for 38 years. She helped to organize the first Lakeview Tenants Council and took an active role in the tenants’ rights movement. She was also a Director of the Community Action Organization (CAO). CAO is a non-profit organized in May of 1965 that serves individuals and families to mitigate poverty throughout low-income communities. Mrs. Cunningham also served as the West Side representative of B.U.I.L.D.(Building Unity, Independence, Liberty and Dignity), a civil rights advocacy group. She was best known for her work during the late 1960s when fights between street gangs were common across the City. She worked with police and teenagers to help stem the violence in her neighborhood. In 1980, she received B.U.I.L.D.’s Outstanding Community Service Award for her youth activities. Sally Mae Cunningham died in January 1990. She is buried in Concordia Cemetery. Shortly after her death, State Senator Anthony Masiello renamed legislation he was proposing as the Sally Cunningham Bill. The legislation was to require the Common Council to to confirm housing directors of the Buffalo Municipal Housing Authority. Masiello said, “Sally Cunningham made decent public housing the focal point of her life.”

Rosetta Petruzzi at the new playground at the Lakeview Development. Source: Buffalo News, May 1995.

Rosetta Ann Petruzzi was also a long-time resident of the Lakeview Housing complex. She lived there for more than 50 years! Rosetta Petruzzi was born Rosetta Scott in Warren, Illinois, in 1926. She came to Buffalo in 1944 after marrying Anthony Petruzzi. She was very active in youth activities at the complex and helped to establish a well-baby clinic in the complex. Along with Mrs. Cunningham, she helped to establish the first Tenants Council. In the mid-1960s, Mrs. Petruzzi served as President of the Lakeview Community Council and helped open a wading pool/splash pad in 1965. The pool had been closed for 20 years at that point. The pool had been shut down due to often needing to be closed for cleaning. Glass was often being thrown into it, so the Buffalo Municipal Housing Authority opted to close it rather than deal with the high cost of draining for cleaning out the glass. Mothers in the Lakeview Council, led by Mrs. Petruzzi, were instrumental in reopening the pool. The mothers agreed to watch the pool from 1pm to 4pm each day. She was quoted in the Buffalo News as saying, “Some people thought that we’d never get a pool closed down 20 years back in operation, but I guess you can get anything if you try long enough.” Mrs. Petruzzi was also active in the Cub Scout Pack at Lakeview Homes and was a den mother to the troop for many years.

Mrs. Petruzzi was active in the Democratic Party and served on the City of Buffalo Citizens Council on Human Relations. This group was formed in June 1963 to help with the problems of employment, education and housing affecting minority groups.

Rosetta Petruzzi stone in Mausoleum at Forest Lawn

In May 1995, the Lakeview Tenant Council and the Buffalo Municipal Housing Authority dedicated a playground and plaque to Rosetta Petruzzi at the complex. The picture above is from the playground’s opening. I was unable to determine exactly where the playground dedicated to Mrs. Petruzzi was located, though I know it is not the playground currently on Fourth Street. If anyone who lived at Lakeview remembers where it was in the 90s, let me know! Mrs. Petruzzi passed away in September 2001 and is buried in Forest Lawn Cemetery.

In the late 1990s, plans to demolish the Lakeview Housing project began to be developed. The reconfiguration of the Projects was part of the federally-funded HOPE VI initiative of the Clinton Administration. There was a lot of controversy involved with demolishing all of the units of Lakeview Housing to replace them. At the time, Lakeview was a little rundown, but most of the units had been renovated, and it was considered “Buffalo’s best family project.” One of the major issues around Lakeview was the substandard housing located in the neighborhood around the projects, as opposed to the actual Lakeview Housing itself. All 660 original Lakeview units were demolished. They were replaced by 360 new townhomes and 74 apartments in a new, four-story senior citizen building. There were also 40 townhouses for ownership. Phase 1 was completed in 2001. The units were designed for families with low to moderate income levels. The new streets in the Lakeview HOPE VI housing were named for Sally Mae and Rosetta, along with Hope Way (for HOPE VI) and Anthony Tauriello Drive, named for Anthony Tauriello, but we’ll learn about him another day – I wanted to focus on the ladies for today! The redevelopment project included a park setting with green space and newly planted trees between the Thruway and Fourth Street. With the exception of a small playground, the site is mostly a grassy field and a berm to protect from the highway. Plans for Ralph Wilson Park (the $110 Million reconstruction of Lasalle Park into a world-class park) include some plans for the Fourth Street site.

A Modern Aerial shows the outline of the former Lakeview Housing, highlighted in blue. Note the new Hope VI housing on the northeastern half of the site.

In 2004, Dierdre William from the Buffalo News described the Lakeview HOPE VI development as if “Someone took Pleasantville and put it in the middle of the Lower West Side.” The new development has a suburban look that’s a far cry from the brick public housing units they replaced. Critics of the Lakeview HOPE VI project stated that while the new units of housing are visually appealing, between the Lakeview houses and Niagara Street, the rest of the neighborhood was still in decline. It was anticipated that residents of Lakeview HOPE VI would open small businesses like daycare and beauty shops. The spin-off development that was expected to happen has been slow to happen.

Next time you’re over on the Lower West Side, or maybe taking the pedestrian bridge into Ralph Wilson Park, think of the Penitentiary and all the people sentenced to the site over the years; think of Louise Bethune, a woman architect breaking down barriers and designing prisons; and think of women like Sally Mae Cunningham and Rosetta Petruzzi who fought to improve conditions for everyone around them. I think sometimes, during months like Women’s History Month, it’s important to remember the major women who accomplished major things, but it’s also important to remember the work of regular women, too. Sally Mae and Rosetta were moms fighting for a better neighborhood. It’s important to remember them and all the other unsung women who’ve been working hard for decades to make their communities better. Happy Women’s History Month! Want to learn about other influential Buffalo women? Check out my roundup of Streets Named after Women here.

Want to learn about other streets? Check out the Street Index. Don’t forget to subscribe to the page to be notified when new posts are made. You can do so by entering your email address in the box on the upper right-hand side of the home page. You can also follow the blog on Facebook. If you enjoy the blog, please share it with your friends; It really does help!

Sources:

- “Mothers Pool Their Efforts to Reopen Wading Area.” Buffalo News. July 20, 1965, p10.

- Hill, Henry Wayland, editor. Municipality of Buffalo, New York: A History 1720 – 1923. Lewis Historical Publishing Company: New York, 1923.

- “Council Urged to Buy Disused County Prison.” Buffalo Evening News. October 25, 1926, p3.

- “Weather Slows Progress on Redevelopment Project.” Buffalo Business First. January 15, 2001.

- “US Not Interested in Old Penitentiary”. Buffalo News. February 28, 1925, p12.

- Buyer, Bob. “Prison Farm Gets County Reprieve.” Buffalo News. June 22,1987, p12.

- Hays, Johanna. Louise Blanchard Bethune: America’s First Female Professional Architect. McFarland & Company, Publishers, Jefferson, North Carolina. 2014.

- Smith, H. Katherine. “Two Streets Memorial to Early Buffalo Lawyers.” Buffalo Courier-Express. March 1, 1942, Sec 4, p8.

- “Local Companies Awarded Most MHA Contracts.” Buffalo Evening News. October 30, 1954, p13.

- “In a Model Prison: A Humane Keeper and His Excellent Methods.” Buffalo Courier. June 1, 1894.

- “Make State Prison Out of Penitentiary”. Buffalo News. March 13, 1903.

- “Winter Resort of Buffalo’s Army of Unfortunates.” Buffalo News. March 1, 1903.

- “Rosetta A Petruzzi, Active in Community”. Buffalo News. September 9, 2001, p13.

- “Housing Cash.” Buffalo Courier-Express. April, 11, 1939, p7.

- “Lakeview Housing Project Site Called Dangerous”. Buffalo Evening News. January 20, 1958, p18.

- “Million-Dollar Canal Parkway Plan is Pushed.” Buffalo Courier-Express. March 7, 1939, p11.

- Downs, Winfield Scott. Municipality of Buffalo, New York: A History, 1720-1923. Lewis Historical Publishing Company, 1923.

- “Inequality, neglect – not just Floyd’s death- fuels protests.” Buffalo News. June 8, 2020, p1.

- “Plan calls for razing entire Lakeview project.” Buffalo News. August 20, 1999, p31.

- Tan, Sandra. “Hopeful Housing.” Buffalo News. September 18, 2000, p1.

- Ashiley, Nii Ashaley Ase. “When Black New Yorkers Decided to Unite for their Own: Buffalo Race Riots of 1967”. Face2Face Africa. June 27, 2019. https://face2faceafrica.com/article/when-black-new-yorkers-decided-to-unite-for-their-own-buffalo-race-riots-of-1967

- Alfonso, Rowena I. “They Aren’t Going to Listen to Anything But Violence: African Americans and the 1967 Buffalo Riot.” Afro-Americans in New York Life and History, Volume 38, Issue 1. January 2014.

- “Citizens Unit Established to Aid Minority Groups.” Buffalo Courier-Express. June 24, 1963, p7.

- “Dynamite Ends Reign of Old Buffalo Pen” Buffalo Times, July 13, 1930

- “Bill Will Honor Sally Cunningham. Buffalo Challenger. January 17, 1990, p7.

- “Mother of the West Side: Sally Mae Cunningham Dies.” Buffalo Challenger. January 17, 1990, p7.

- Documents of the Assembly of the State of New York, Volume 13. New York State Legislature, Assembly. 1892.

- Williams, Dierdre. “A New Hope for Public Housing Suburban-Looking Community Rises on Vestige of Lakeview Homes.” Buffalo News. June 17, 2004.